Reviewed by Jordan Frazer

If you look at Ringo Starr’s vocal contributions to The Beatles’ albums, it’s no wonder that he cited country music as his favourite genre in his recent interview on Jimmy Kimmel Live: ‘…we got a three month job and we all changed our names. I thought…Ringo – cowboy’.

Ringo’s always just wanted to be a cowboy. And Nashville loves him like a son. He was on the show to promote Look Up – his first full LP since 2019. Recorded mostly in Nashville, Tennessee and released (in hard copy and digitally) on 10th January 2025, Look Up contains 11 new original songs, is produced by country powerhouse T Bone Burnett and features musical collaborators Molly Tuttle, Billy Strings, Lucius, Larkin Poe and Alison Krauss. Oh, and it’s also Ringo’s first ever No.1 album.

Track by track

‘I’m on the train to Liverpool…I have Ringo Starr’s new record as my companion…As each track concluded, I found myself sending a short message to my brother T Bone Burnett…’ Adopted-Scouser, Elvis Costello’s liner notes to Look Up provide a real-time, track-by-track reaction to the 11 songs. It’s a style of review that matches the immediacy of the record. A record from everyone’s favourite adopted-cowboy. And so, when tasked with reviewing it myself, that’s what I did

1. Breathless

The boy from the Dingle’s drums lead you straight in, and there’s no doubt you’re in Nashville. Stylistically, it leans a little too-heavy into the blues and so is not the strongest opener, but the ambience it creates forgives those compositional shortcomings: it’s like you’ve been dragged off the street into an eternal barn dance, Ringo on the stage, backed by his band of virtuoso outlaws. ‘Breathless’ establishes

the performance themes of the album: attractive arrangements, played with feeling, never over produced, a live sound: quintessentially Country & Western.

A busy acoustic guitar, like something from a J.S. Bach fugue, transports you deeper into hillbilly territory, before a backwards electric guitar and the jolt of the under-used lyric ‘beguiled’ remind you you’re listening to Ringo, the drummer from The Beatles.

2.Look Up

The title track brings you Molly Tuttle’s first named appearance. The first female winner of the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Guitar Player of the Year (2017), her involvement was always going to add something special, and her ethereal harmony lines dance atop Ringo’s plaintive delivery to elevate the song to the heights of its lyrics. Opening with a guitar tone not unlike the ending of ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ – a psychedelic lens on countrified rock which evokes Gene Clark’s 1974

album No Other – it’s the least cowboy song in the collection. But it’s POP-TASTIC. And it’s got cosmic lyrics to boot: ‘the future never comes and the past has passed, look up’. It’s a sentiment that traces a line through Ringo’s back catalogue (see 2008’s Liverpool 8), but it’s better-distilled here – you really believe him. A song which takes on a greater significance in the aftermath of the LA fires: ‘there’s a burning fire leading through the haze’. You might’ve been reserving judgement so far, playing your cards close to your chest? Two tracks in, you’re settled. You’ve confidence in the band, in the playing, in the integrity of the songs…and you’ve confidence in the molasses-rich tones of the man with the microphone. It’s gonna be all aces from here

on in.

3.Time On My Hands

A piano thud and bright acoustic strum make you think of Ringo’s best: ‘Photograph’, before they dissolve into Paul Franklin’s gorgeous and rueful steel-guitar which weaves its way in and out of the arrangement like bourbon from a bottle leaving an indelible, forlorn imprint behind. It’s cinematic Wild West-regret: your most cowboy song yet… but it’s also where Ringo sounds his most Scouse, on words like ‘learned’ and ‘burned’.

4.Never Let Me Go

Oh no! You were too quick on the draw! THIS is your most cowboy song yet! You’ll find the verse a little plodding and the song doesn’t really develop, but the Johnny Cash-like repetitive trance of its chorus will have you side-stepping in the most mesmerising line dance routine your mind can muster. On an album that (up to now) sounds almost-always authentically-American, the harmonica playing is all

British-invasion: it could be Mick Jagger and Keith Relf exchanging blows down The Marquee Club circa 1964. And if you’re anything like me, ‘Never Let Me Go’ will have your favourite vocal moment on the album: there’s something hat-tippingly perfect about Ringo’s delivery of the line ‘reckless lies and sad farewells’.

5.I Live For Your Love

Molly Tuttle’s haunting harmony returns: a ghost of the past to the lyric message of living in the present. A major-led melody with minor inflections, like a doe-eyed glare across a dancehall. Slow, but very sure of itself. Simple. Effective. Beautiful. Doesn’t outstay its welcome. A neat closer to Side A on the vinyl copy.

6.Come Back

Hold your horses. THIS IS THE COWBOY SONG. Like a Spaghetti-Western re-imagining of his solo scene in A Hard Day’s Night, you can’t help but picture Ringo trotting his way down-river. The very thought of it – that you’re listening to the same man, 60 years on, in such strong voice and with peace and love in his heart – is reason enough to buy this record. It’s almost bluegrass, with a tempting

chromatic riff and some exemplar whistling (courtesy of the man himself, so important to the song that ‘whistling’ is listed before ‘lead vocals’ on Ringo’s credits for this one). It’s surrealist lyric ‘one un-cloudy day’ could be straight from The Goon Show playbook of his youth, or a call back to some of that wartime scouse wisdom we’re always hearing Ringo remembering of Merseyside.

7.Can You Hear Me Call

You’re over halfway now and this is a well-placed second track on Side B, because it’s probably the skipper on the album (if you have to elect one). A nice-enough duet with a literal call and response. There are almost 53 years between the two protagonists of this love story, but it doesn’t feel uncomfortable. Tom Jones and Cerys Matthews this is not! The guitar motif will remind you of ‘Sunshine Life For Me (Sail Away Raymond)’ from 1973’s Ringo album. A nice touch, and worth a listen if only for the nostalgia of that. Why’s the title missing a question mark? Don’t worry about it, you’re in Nashville.

8.Rosetta

…the irresistible groove is heavy and boundless, with overdriven guitars making a dirty descent into verse one. ‘The sun’s low in the sky’. It’s redolent of early-Led Zeppelin and it’s another line dancer. But where ‘Never Let Me Go’ was sunrise,

‘Rosetta’ is the first suggestion of sunset over Tennessee. ‘We could always stop the clock’ – the sound of liquor, smoke and of time standing still as the saloon doors are slammed and Ringo rides out of town. But in this story of two old lovers, the star-spangled lyrics reveal that it’s her who’s abandoned him. ‘Rosetta, where you been so long?’ This might just be your favourite, musically anyway.

9.You Want Some

Another missing question mark from a title? No, it’s clever. It’s not a gun-slinging challenge, it’s a statement. Ringo is telling you that you want some: he’s ‘…got love to give. Baby, that’s a-better than none. You want some.’ He only asks you ‘do you want some?’ at the end, and I’ll tell you what, if you know what’s good for you, you do want some. You might find this one a bit plodding as well, but it’s not cumbersome and he sings it well. The ending will bring to mind ‘You And Me (Babe)’ – the closer of Ringo (1973) – and, for that reason, it feels like it should be the last song, bringing down the jalousies on a fine album. Possibly a little out of place at Track 9, but when you hear where it’s going next, you’ll realise that it was an ending of sorts.

10.String Theory

The title alone takes you on a trip somewhere else to end Ringo’s long player. A little slice of psychedelia for our age of anxiety. ‘Everything dreams and radiates beams’. It’s all connected. You just feel safe. And Ringo is hip and wise to it. A nice drop on ‘Everything cries’ shows a vulnerable side to an otherwise uplifting and anthemic song and the musicianship is enchanting: a chiming, Byrds-like cacophony, plucking its own 12-string theory which will be hard to disprove. A great cosmic segue into the lasting remarks of the album’s conclusion.

11.Thankful

Alison Krauss makes an appearance just in time for sundown: the one track on the album penned by Ringo. And it’s autobiographical, but it’s not on the nose. It doesn’t mention meeting John, Paul and George or Rory Storm or the Maharishi. ‘I had it all, then I started to fall’. If you’ve ever read-up on Ringo’s struggles with substance abuse and depression, or you’ve had similar struggles yourself, this will resonate – it’s the sound of an almost 85-year old man, decades younger than his years in both

voice and appearance, happy with his lot, and ‘thankful’ for his fortune. Not his wealth, but his good fortune: his second chances at life and his loved ones. He’s singing to Barbara. ‘I needed a friend to help me along…now I have good days…and it’s a beautiful day here in California’. You might think the lyric ‘thankful you are here’ would’ve been better as ‘thankful you are near’ so as to avoid the repetition-rhyme from the previous line. That’s until you hear the pay-off. The album’s final

thought: ‘You are here’ – a mantra from the meditative mindset he’s carried with him for over 50 years. And it’s a perfect tonic from the world we’re in right now.

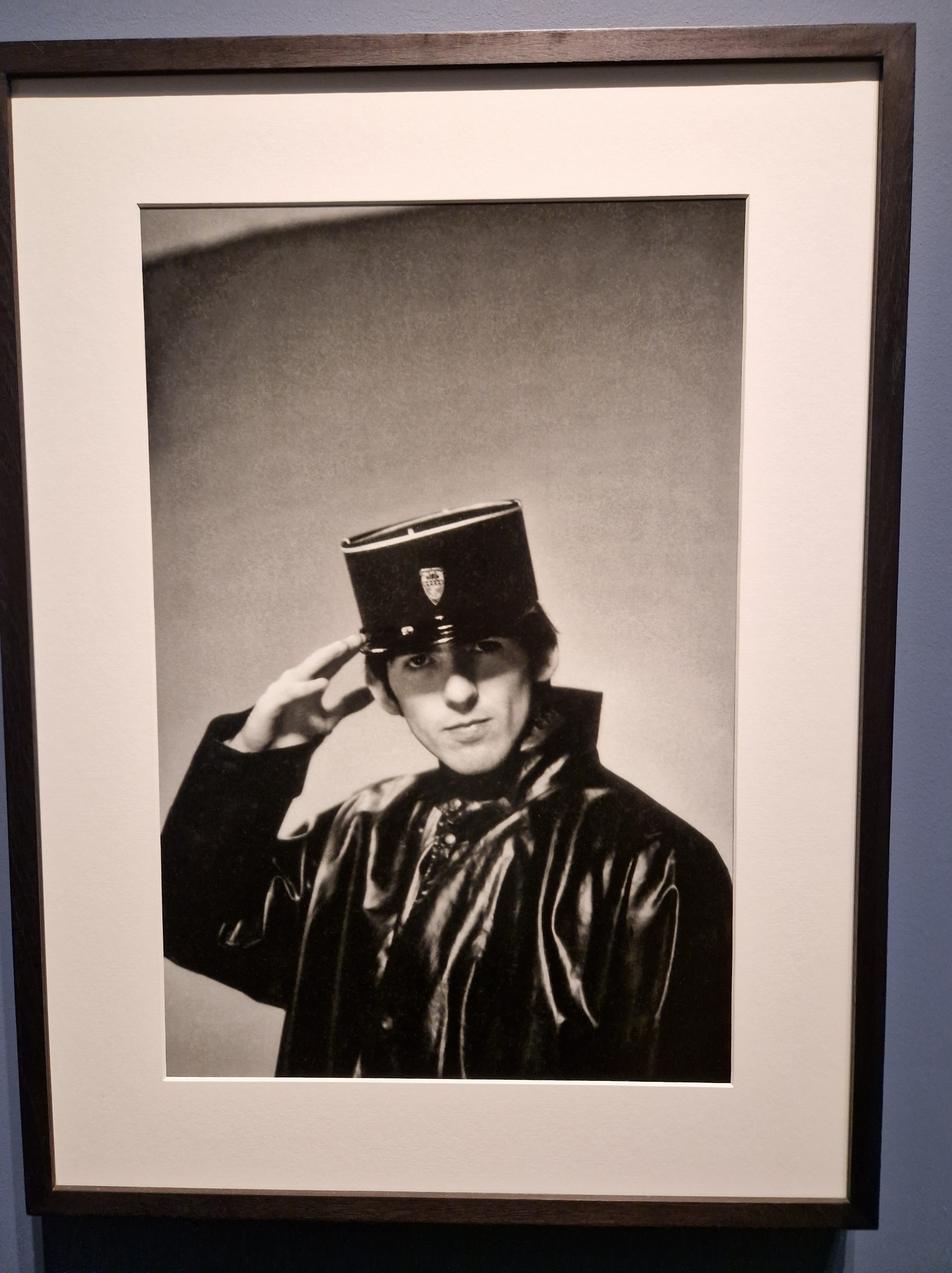

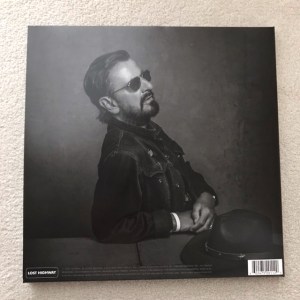

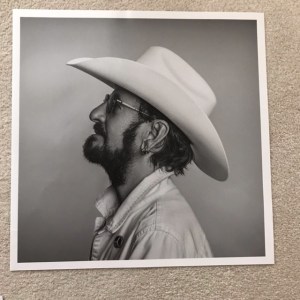

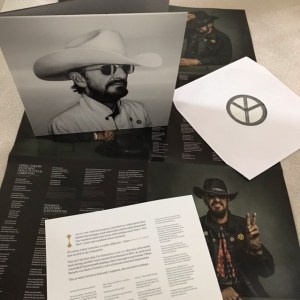

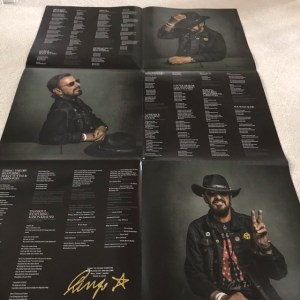

The Vinyl Package

The Lost Highway vinyl edition is smart. A monochrome gatefold, bookended with candid snaps of a youthful Ringo in various Western get-up, hallmark CND badges and mentions of peace and love opens to an elegant typeface in white and gold. The text is keen to remind us of T Bone Burnett’s involvement. And I suppose it’s warranted, because he wrote most of the material, played on a lot of it and produced

it all. He doesn’t steal Ringo’s thunder, though.

Just like the music behind the titles, the colour is all inside. A glossy lyric sheet unfolds to an A2 poster with another photograph of Ringo, this one posed: two fingers of peace held to the camera and a smile across his mouth that you’ll be sharing by now. The stars, on his shirt and all-over the album, suggest a better version of America than the one we have. It’s a hopeful image in so many ways.

And, importantly, Ringo’s collaborators are given due credit and a message of thanks: ‘I want to thank everyone who played on this record. Well done T Bone! Peace & Love.’

Ringo’s Round-up

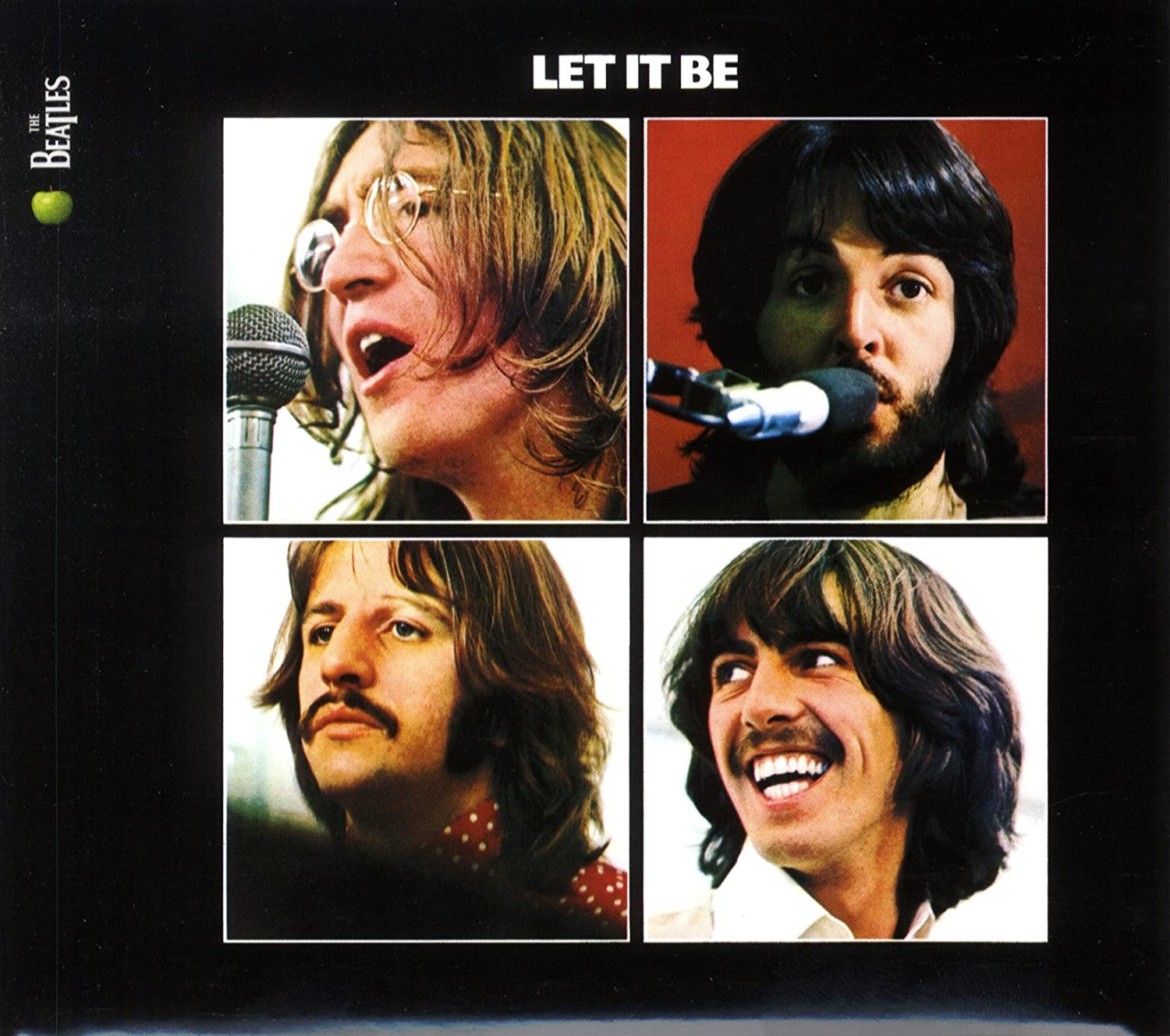

Anytime I drop the needle on a new Fab release, there’s a knot where my stomach resided only seconds earlier – equal parts excitement and nerves. I just want it to be good. I don’t need anything ground breaking; Revolver’s still got that covered. I don’t need anything aspirational; Sgt. Pepper stands alone. I don’t need anything as expansive as All Things Must Pass or as eclectic as Ram or as political as Some Time In New York City or as glitzy as Sentimental Journey. I just want something that doesn’t affect the legitimacy of the existing canon. Something passable. I had the same feeling with McCartney III. And, strangely, Look Up elicited a similar response in me which is growing stronger with every spin.

The lyrics aren’t ground-breaking, the musical ideas aren’t exactly aspirational, the song structure isn’t eclectic, the running time at 36:57 isn’t expansive, other than the inescapable notion of America, it’s not a political album, and the artwork – although tasteful – isn’t particularly glitzy. But all of that’s also its biggest draw. It’s unfussy, confident, tasteful and relevant. It maintains a stylistic identity which holds, without resorting to parody. The lack of fade-outs, consistent use of instrumentation and just the right amount of imperfection make Look Up feel like a live band playing a set from start to finish: a running order with a sunrise-to-sunset arc, ending on Ringo’s heartfelt and positive message, wrought from a lifetime of experience.

The Beatles Handbook rating: 5 Stars

Essential tracks:

Look Up

Time On My Hands

Never Let Me Go

Rosetta

Thankful

P.S. as I was tidying up this article for publication, I was listening to Look Up on Spotify. After spending so long with the hard copy, I don’t remember a time when I’ve missed the tactility of vinyl as much. But streaming it offered a nugget of validation the vinyl could never: when the album finished playing and my Spotify algorithm side-stepped to a shuffle befitting what I’d just listened to, its first choice was ‘Loser’s Lounge’ from 1970’s Beaucoups of Blues. And it could’ve been cut from the same roll of studio tape. From Nashville to Nashville, 55 years apart, what a

vote of confidence. A gold star for Mr Starkey.

Written by Jordan Frazer. Follow him on Twitter at @TheStylusMethod and find out more about the band at Bandcamp