The song ‘suite’ plays a major role in The Beatles canon, both band and solo eras. For many, it the form will forever be associated with McCartney and Wings. From ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’ to ‘Medley: Hold Me Tight/Lazy Dynamite/Hands Of Love/Power Cut’ to ‘After The Ball/Million Miles’ and ‘Winter Rose/Love Awake’ or the pocket symphonies of ‘The Back Seat Of My Car’ and ‘Band On The Run’.

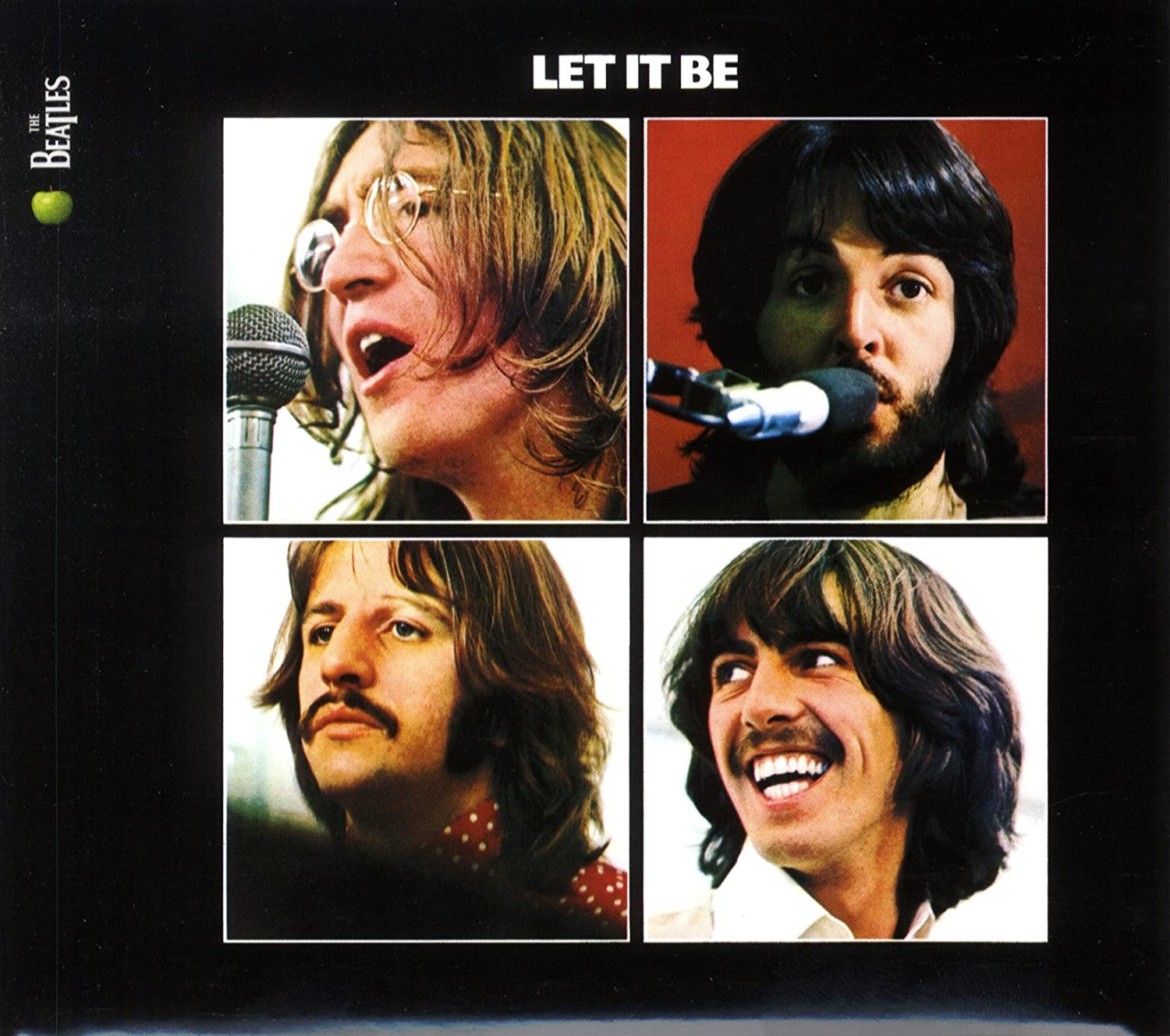

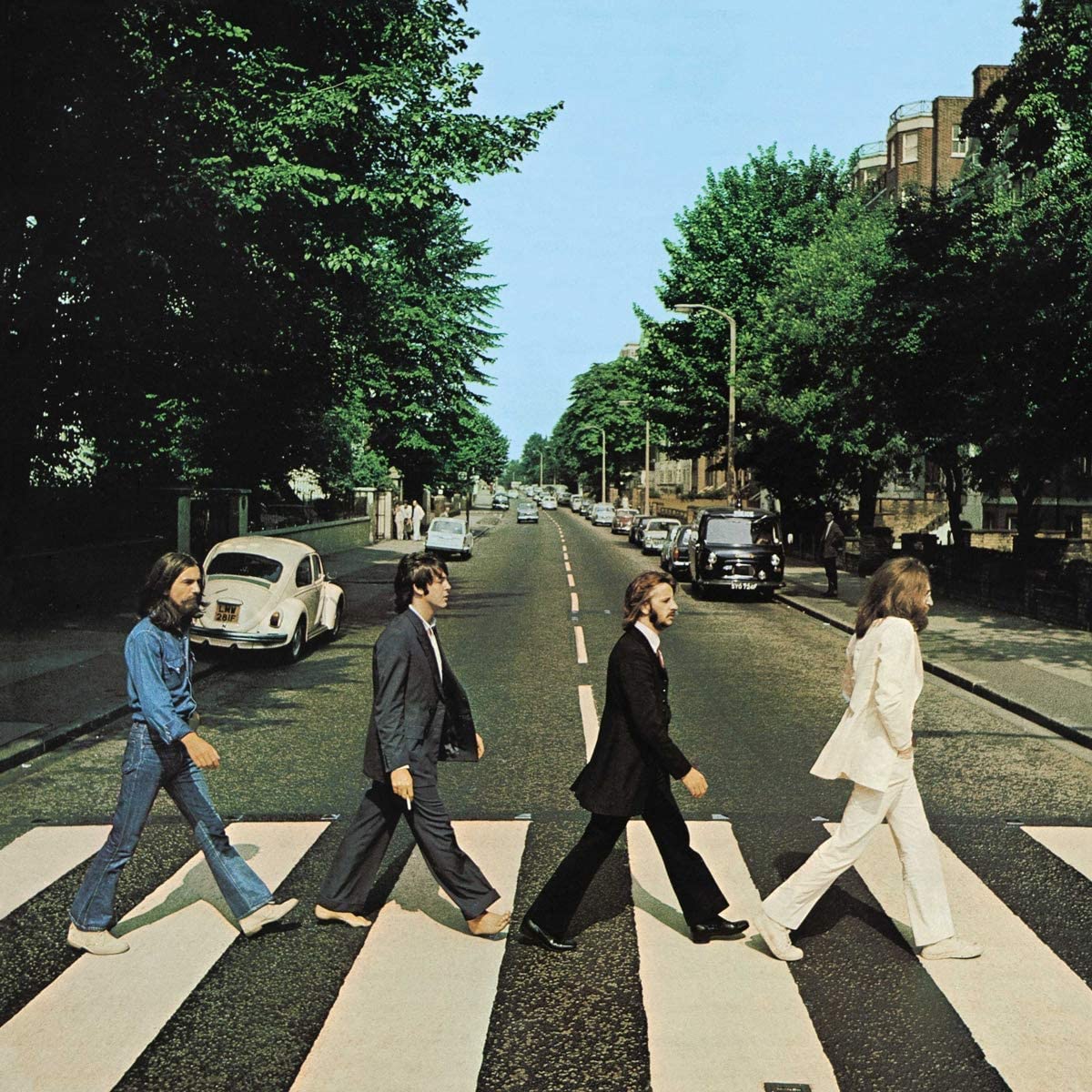

All of that stems from the fragmentary glory that is Side Two of 1969’s Abbey Road, the musical definition of a whole that is greater than a sum of its parts. It’s arguably the aural summit of The Beatles’ recorded work. However, the finale of the album almost called ‘Everest‘ was derided by John Lennon as ‘unfinished songs all stuck together. Everybody praises the album so much, but none of the songs had anything to do with each other, no thread at all, only the fact that we stuck them together‘ (John Lennon Playboy interview with David Sheff, September 1980 (published January 1981)). Lennon’s criticism is harsh, but there is truth in it. While ‘Abbey Road Medley’ ( Side Two of Abbey Road is colloquially known as the ‘Abbey Road Medley’, however, the 2019 box-set reissue also refers to it as ‘The Long One’) is a delight, befitting the end of a decade and the band that defined it, there is an earlier near-perfect track sequence in The Beatles’ canon.

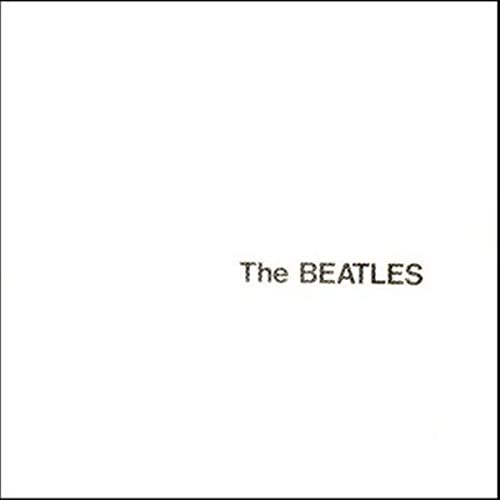

Side Four of The White Album is often overlooked and even ignored as the ‘weird’ side; evidence that the 1968 thirty-track behemoth should’ve been a two-sided LP. But it might just be the best example of a song suite in popular music. Individually, ‘Revolution 1′, ‘Honey Pie’, ‘Savoy Truffle’, ‘Cry Baby Cry’, ‘Revolution 9’, ‘Good Night’ are unlikely to make anyone’s Friday night playlist. If you met someone at a party who said that any one of them was their favourite Beatles track you’d make your excuses and head to the bar.

One might even go as far to say that not one of the tracks stands out on The White Album. The popular verdict: ‘Revolution 1’ is a less-exciting cousin to the raucous, electrifying B-Side to ‘Hey Jude’. ‘Honey Pie’ personifies (in name and substance) the sickly-sweet nadir of McCartney’s pastiche and ‘Savoy Truffle’ is another forgettable ‘Harrisong‘, meaninglessly listing the contents of a chocolate box and warning against the perils of tooth decay. ‘Cry Baby Cry’ is a glorified lullaby based on an advertisement, a continuation of post-Rubber Soul Lennon laziness, ‘Revolution 9’ is a mess of noise, a waste of vinyl space at 8 minutes, 22 seconds. Ending the album with ‘Good Night’, a Ringo vocal is a bad move to say the least, exacerbated by Disney tremolo strings and saccharin lyrics.

Side Four of The White Album, ‘You can count me out (in)’. Right?

Wrong.

A Doll’s House

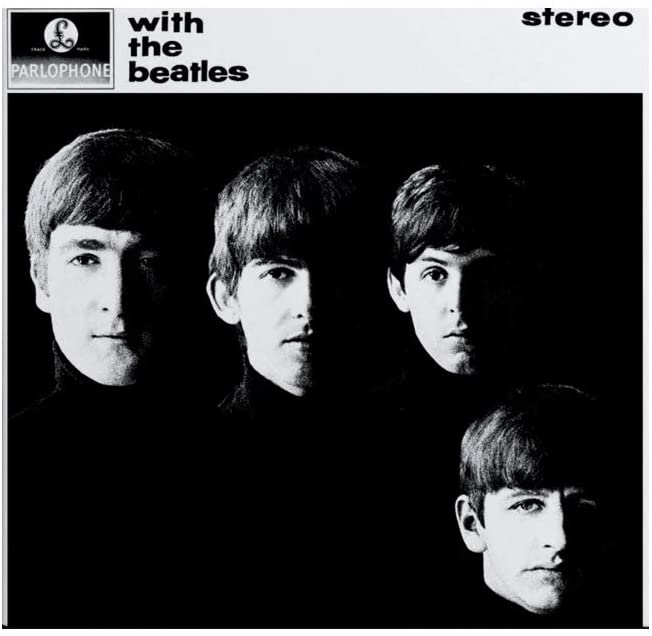

1968’s The Beatles (whilst this is the official album title, it quickly became known as The White Album for its minimalist cover) was almost called something very different . Had it not been for British psychedelic group Family’s debut LP Music In A Doll’s House released in July of the same year, the Beatles’ only double was slated to be ‘A Doll’s House‘.

Imagine that. A creepy Victorian miniature mansion with 30 rooms, one for each song. Each behind an auspicious door with which, upon opening, you might be met with anything from a dose of pastiche surf rock (‘Back In The USSR’), a game of self-referential Beatles Cluedo (‘Glass Onion’), a paean to mating primates with one of the most underrated rock vocals of all time (‘Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?’), a song about a sheepdog (‘Martha My Dear’), a blackbird (‘Blackbird’) or a Raccoon (‘Rocky Raccoon’), a dystopian warning à la Orwell (‘Piggies’), an anti-hunting anthem? (‘The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill’), a slagging off of Sir Walter Raleigh (‘I’m So Tired’), a slagging off of the Maharishi (‘Sexy Sadie’), a slagging off of ‘you all‘ and the invention of 1970s FM radio rock (‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’), the world’s first heavy metal song (‘Helter Skelter’), a bassline played with the mouth (‘I Will’), a Psych/hard rock/gun magazine Doo Wop (‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’), a song for anyone with a birthday this year (‘Birthday’), Ringo’s songwriting debut country groove (‘Don’t Pass Me By’), a cowbell maybe even too prominent for Christopher Walken in the Saturday Night Live sketch ‘More Cowbell’ which aired on 8th April 2000 (‘Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except For Me And My Monkey’), a blues dirtier than a Woodstock puddle (‘Yer Blues’), potentially androgynous reggae (‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’), an attempt to coax Mia Farrow’s sister from a hut (‘Dear Prudence’), the musical and spiritual meeting of the two great loves of John’s life (‘Julia’), an acidic glimpse of mantra madness (‘Wild Honey Pie’), pre-‘Country Dreamer’, country-dreamer-Paul (‘Mother Nature’s Son’) or drums so distant and heavy they sound like they could’ve been recorded in the Himalayas six months earlier, the sound only just reaching you now (‘Long, Long, Long’).

After the pop side (Side One), the folk side (Side Two) and the rock side (Side Three), Side Four is ‘The Doll’s House Side‘. It should be noted that what follows is not a proclamation that Side Four of The White Album is a predetermined concept or even, on a song by song basis, necessarily how The Beatles intended to convey meaning through its contents. However, it is an interesting way in which you can listen to it and, more importantly, it’s a lot of fun; a manual for a new way to try the songs you may have underestimated by the band you thought you definitely hadn’t.

A childlike revolution

Revolution 1

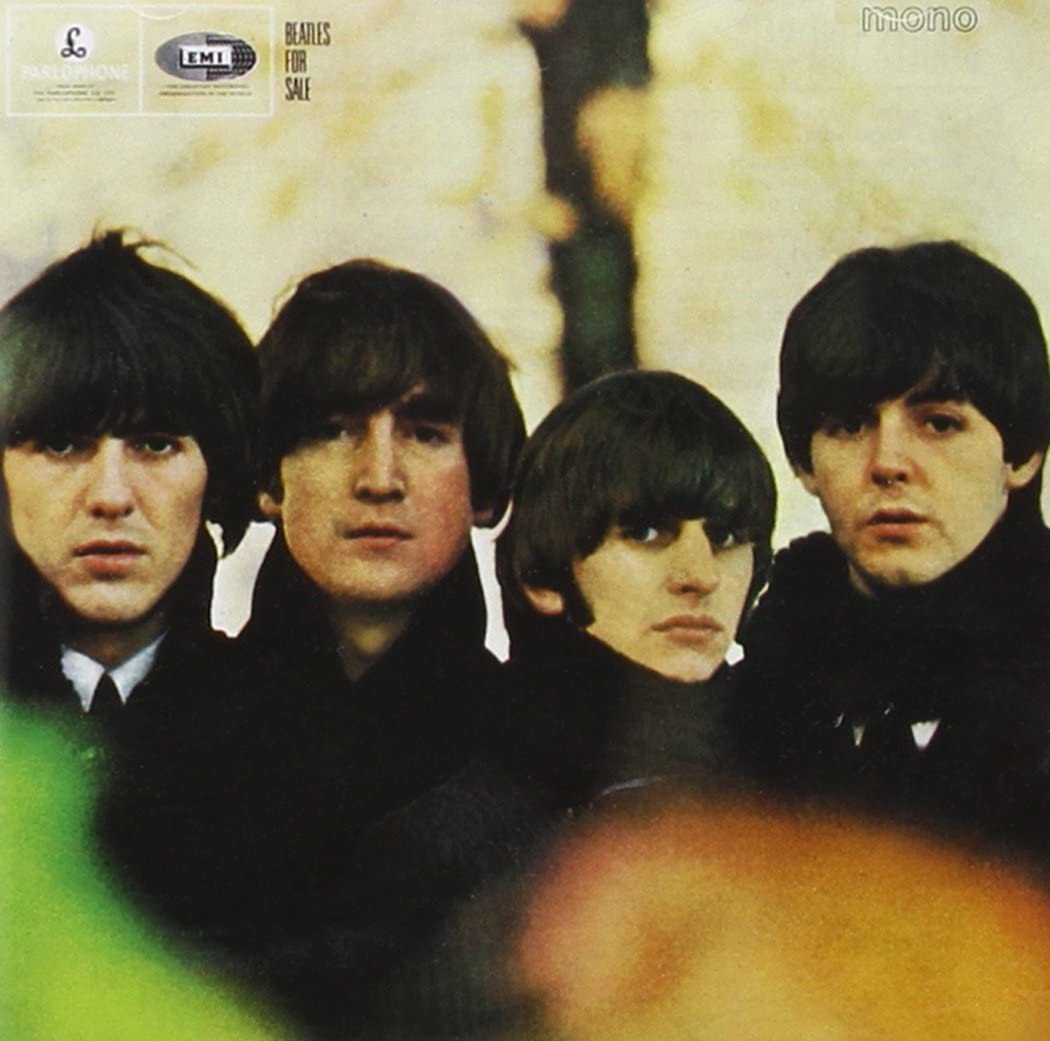

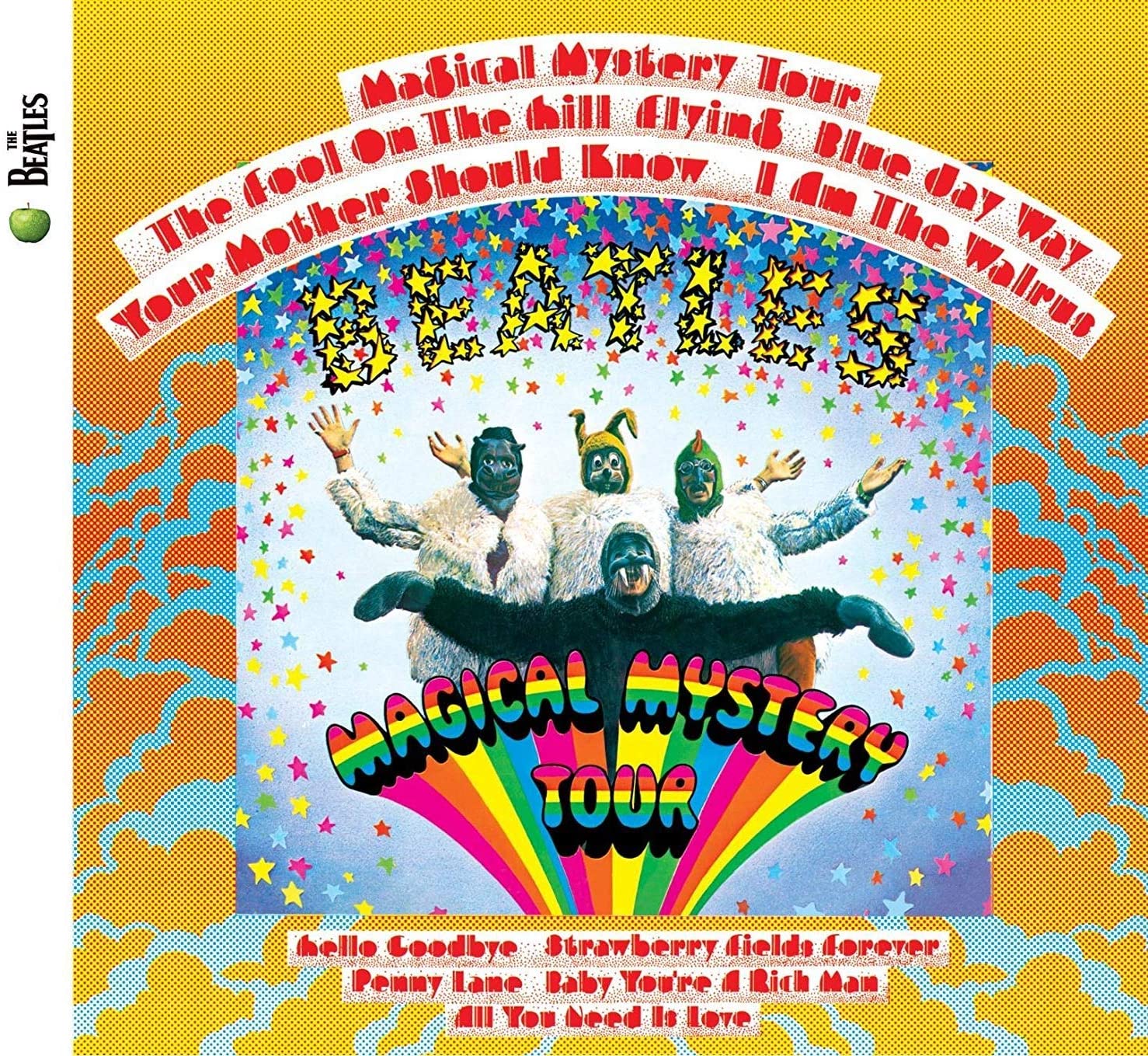

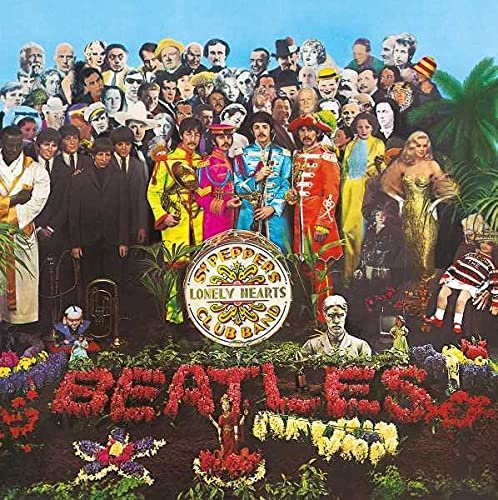

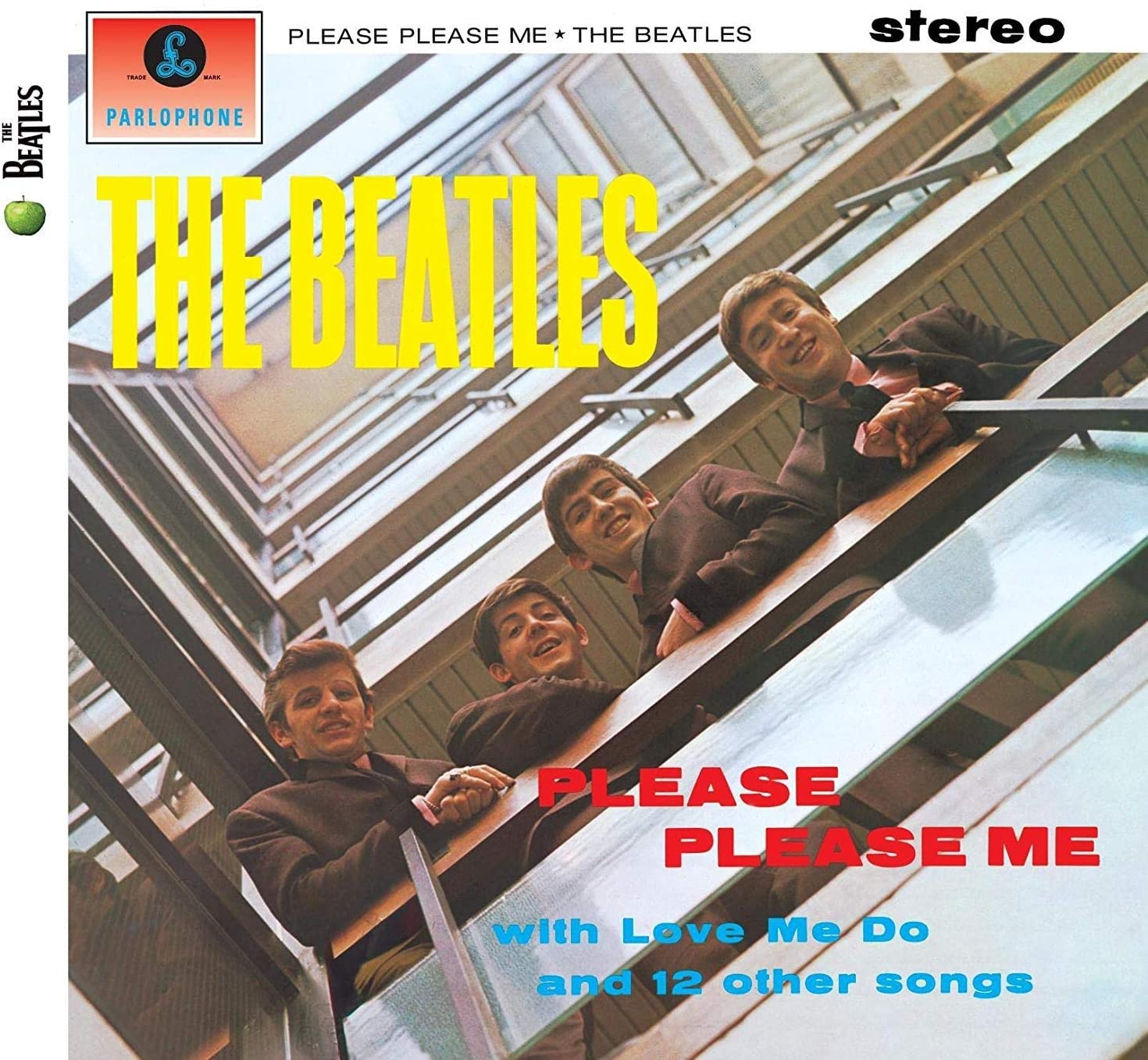

Recording sessions for The White Album began in EMI Studio Two at Abbey Road on Thursday 30th May, 1968. Having recorded the extensive Esher Demos at George’s Surrey bungalow, Kinfauns, the boys had over forty songs from which to build the official follow-up LP to Sgt. Pepper (Magical Mystery Tour was only released as an EP in the UK. Interestingly, 1968 is the first instance since 1963’s Please Please Me where The Beatles had more material than was required to fill an album and the only time where all of that surplus was original material). ‘Revolution’ was selected as the first of the new batch to be recorded and the work done on this day gives us two of the songs on Side Four of the eventual LP (Take 20 produced ‘Revolution 1’ and its extended outro provided the structure of ‘Revolution 9’).

The White Album is inextricably linked with The Beatles’ pilgrimage to Rishikesh, beginning in February 1968. Although reference to the Indian experience justifies the acoustic timbre of a significant portion of the album, it is perhaps just as prudent to consider the album in the context of the year of its creation which, like 1967, is a year in which its music is difficult to separate from its events.

By late ’67 it was becoming clear that the hippie utopia wouldn’t materialise on either side of the Atlantic. The Haight-Ashbury had descended into “ghastly drop-outs, bums and spotty youths, all out of their brains” (George Harrison’s comment on witnessing San Francisco in 1967, included in Derek Taylor’s memoir ‘As Time Goes By’ (1973)). US death tolls in Vietnam were at their highest in 1967-1968 at more than 28,000. On 17th March 1968, approximately 25,000 people gathered outside the US Embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square to protest the US involvement in Vietnam, resulting in riots. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated on 4th April in Memphis and Robert Kennedy on 6th June – a week into The White Album sessions – in Los Angeles.

It is, therefore, hard to ignore the notion that, in beginning work on their new album, The Beatles were following past practice and reacting to the world outside Abbey Road, setting ‘Revolution’ and its subject matter as The White Album‘s manifesto.

Whether discovering The Beatles in real time or later you were likely already familiar with another version of the song; the distorted guitar and screams version which backed ‘Hey Jude’ as the first Beatles’ release on the Apple label (26th August 1968). ‘Revolution 1’ was, and to a degree still is, therefore, a surprise. It has broadly the same arrangement as the B-Side but is much slower, less electric and with an almost comical doo-wop backing.

Whereas the single version ‘Revolution’ embodies the idealised uprising from the perspective of its subscribers and participants (perhaps the Grosvenor Square crowds) ‘Revolution 1’ is more like a middle-aged, bowler-hatted Londoner, let’s call him Harold, walking through those 1968 scenes. Passively passing through Ladbroke Grove, he is sympathetic to the cause but feels the need to point out why it is so easily undermined by those so inclined with the lines ‘if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow’ and ‘if you want money for people with minds that hate, all I can tell you is brother you’ll have to wait’.

The protagonist does not necessarily feel part of the ‘Establishment’, but his age lends itself more readily to the established order than to subversion of it. This generational gap creates an unbreakable apathy in the older generation, in which its flippant treatment of the younger generation and its dogmatic belief that to ‘change the world’ is an impossibility is acutely distilled in Lennon’s sarcastic vocal delivery: ‘we’re all doing what we can’.

Honey Pie

‘Honey Pie’ is disadvantaged by its place in the The White Album track listing. Firstly, after three-and-a-bit sides of largely unusual music, a listener may be fatigued. Secondly, we’ve already heard ‘Wild Honey Pie’. That either means we’re intrigued by what a similarly-named song has to offer (not a great deal as it turns out) or, if you hated ‘Wild Honey Pie’, ‘Honey Pie’ is already tarred with the same brush. Thirdly, ‘Honey Pie’ naturally falls within the McCartney music hall catalogue of which this album already exhibits a superior representative in ‘Martha My Dear’.

But maybe, just maybe, ‘Honey Pie’ isn’t a music hall pastiche. Harold arrives home. He’s off the streets of a crumbling London and into his sanctuary where, if he likes, nothing ever changes. He pours himself a cognac and places the gramophone needle on his favourite 78; the sound of the 1940s, his golden generation. He dreams of Hollywood and romance; the song’s heroine evokes the great loves of his youth before he settled down into a settled job and a settled life. ‘Honey Pie’ is an exploration of his delusional apathy and selective ignorance of the reality of things. In providing a stark contrast to the breakdown of the psychedelic generation’s attempts to change the world, it represents the very people best-placed to assist yet whose only act was to turn their backs and turn up their radios to drown-out the sound of a world about to erupt outside the four walls of their homes.

Savoy Truffle

The compressed horns of ‘Savoy Truffle’ lay a fanfare foundation for the entry of the family’s children into the front parlour with their mother holding a new baby. They’re excited to see their father, home from another very important day in the very big city making the world go round. They’re clutching at boxes of chocolates and grinning from ear to ear. The Mackintosh’s ‘Good News’ varieties listed in the lyrics contrast with the bad news about to unfold outside. Shinily-wrapped in a tooth-decay warning, Harrison’s metaphor is dual-purpose for the loss of the innocence of childhood by adopting those ‘adult’ ideas of security, self-preservation and greed and, with it, the decay of progressive society. An arguable theme of the album is the notion that once such innocence is lost, it is irretrievable: ‘You might not feel it now, but when the pain cuts through you’re going to know and how the sweat is going to fill your head, when it becomes too much you shout aloud’, sings George in a sentiment that goes beyond a mere call for a Clapton root canal (the genesis of the song was friend (and White Album contributor) Eric Clapton’s love of chocolates).

Cry Baby Cry

Father sings a lullaby to his family, ‘cry baby cry, make your mother sigh’. The man of the house is happy to admire his family at a distance but without adopting direct responsibility; they are one of his marks on the world (‘the children of the King’) and it is enough, to him, that he graces them with his presence. His wife is ‘old enough to know better,’ supposing that age equals wisdom, a view that the songwriting is questioning here. The enemy to progress is the established order, the staid way of thinking, risk-averse sensibilities and the only burning desire, seemingly, a one to ‘grow up’.

The characters in ‘Cry Baby Cry’ are obvious symbols of this established order. The Duke is ‘having problems with a message at the local bird and bee’. Perhaps he is physically barricaded in his local pub by active participants in the peaceful revolution. Perhaps the childlike suggestion of the ‘birds and the bees’ presents him as emotionally barricaded from showing his wife the love she deserves. She, the Duchess, seems to be elsewhere, maybe invited to the family home for tea after the children go to bed. ‘Cry Baby Cry’ is The Last Supper for the establishment while the revolution rages on the other side of the draped windows.

The hidden track between ‘Cry Baby Cry’ and ‘Revolution 9’ harnesses the ethereality of the former, souring in its fading notes toward the apocalyptic feel of the latter. ‘Can you take me back where I came from?’ sings Paul with reverberant acoustic guitar accompaniment. The final verse of its parent track describes ‘a séance in the dark with voices put on specially by the children for a lark’. Is this, the child track, the voice of one of those children larking about? Or is it the voice of a ghost trapped in the Ouija board and summoned up during the séance? The repeated one-line lyric could be heard as a plea by the adults in the room to revert to the innocence and security of their own childhood, but they know too much and find themselves helpless. They are the dolls in a Doll’s House.

Revolution 9

‘Revolution 9”s foray into musique concrète is the sound of the revolution itself. John Lennon has said as much: that the song is ‘an unconscious picture of what I actually think will happen when it happens; just like a drawing of a revolution’. The Lennon/Harrison collaboration is possibly better-described as a Lennon/Harrison/Ono collaboration, significantly influenced by an absent Beatle first-interested in avant garde experimentation and the use of tape loops, Paul. In any event, the supposedly random collection of sounds throws up some interesting ideas.

The ‘Number 9, Number 9’ refrain is not reminding us Paul is dead. It is the Doll’s House gramophone sticking; the party is almost over and the world outside is falling apart. ‘Revolution 9’ evokes the disconcertion of a semi-dream state, its split-screen narrative flicking between what is going on inside and outside of the Doll’s House. The introductory exchange between George Martin and Alistair Taylor apologising for not buying a bottle of claret, followed by the exclamation of ‘cheeky bitch’ makes the listener feel they’re eavesdropping on a middle-class conversation in the [pineapple] heart of Dinner Party Society.

The crazed female laughter is the Duchess from the previous song, ‘always smiling and arriving late for tea’. The discussions of the ‘price of grain in Hertfordshire’ and ‘financial imbalance’ are the gentlemen discussing matters of a fiscal nature over a cigar while the baby cries in the corner for its mother’s attention. Outside, the prophecies of ‘Revolution 1’ are coming true with riots and gunshots and cries of “Right, Right”. George’s repeated ‘El Dorado’ is foreshadowing the fall of the empire around the Doll’s House next to his sombre double refrain ‘Who was to know?’ suggesting a tragic meaningless to all this violence.

As the sound collage reaches its chanting climax, its most famous line, spoken by Yoko, ‘if you become naked’ is confirmation that the regression to a childlike state is the answer – the true revolution is not political, economic or violent but is to reject baseless ‘adult’ ideas. The dream isn’t over, it’s just a different dream to what we thought was the answer in 1967.

Jonathan Gould wrote that ‘Revolution 9’ is ‘an embarrassment that stands like a black hole at the end of the White Album’. But it isn’t at the end of The White Album and the track that closes out the LP is far from a black hole.

Good Night

No other song from the Esher Demos would be a more appropriate finale to this strange and wonderful cabinet of curiosities and, sometimes, there’s no other song in the world that I’d rather listen to than ‘Good Night’. The comfort of Ringo’s voice cascades from the record like a warmed blanket unfurling, inviting the listener to feel like a child being tucked-in for a sound night’s sleep by its singer. And that is why it’s perfect. None of the other Beatles could have sung it convincingly, yet Ringo is earnest. ‘Good Night’ is the foil to ‘Revolution 9’. In the same way that the gravity of Revolver‘s closer is tempered by its comic title, The White Album‘s final song sweeps away any pretension left hanging after ‘Revolution 9’, yet simultaneously progresses the apparent theme of Side Four, resolving it in the only way The Beatles knew how, with positivity. Within the safety of the child mind, the regression from the chaos of the adult world is complete and maybe it is ‘gonna be alright’.

Take this, may it serve you well

The resurgence in popularity of the vinyl record is encouraging for the preservation of the ‘album’ as an art form. If artists are to write and record successful ‘albums’, attention must be paid to track sequencing and how a side of vinyl flows, develops, balances light and shade, maintains interest and leaves a lasting impression. Whereas Side Two of Abbey Road is a masterclass in sonic knitting, Side Four of The White Album is a thematic opera: A Doll’s House. If you’re striving for a new way to listen to The Beatles, I invite you to revisit Side Four and see what you think it’s all about. After all, it’s all in the mind you know.

Written by Jordan Frazer. Follow him on Twitter at @TheStylusMethod and find out more about the band at Bandcamp