Review coming soon

Now and Then – the last Beatles song

Review coming soon

Why did The Beatles break up? On the face of it, that we’re still asking the question more than half a century after the fact might seem a little strange. But this is The Beatles we’re talking about, the most important and picked over band in the history of recorded popular music, of course we want to know why they didn’t last beyond the 18 August 1969, the last day they recorded together.

Or was it 20 September that year when Lennon told his bandmates he wanted a ‘divorce’ (it’s worth remembering that, by this point, Lennon had already released ‘Give Peace a Chance’ as Plastic Ono band earlier in July and recorded the follow up ‘Cold Turkey’ on 30 September which was number 14 in the charts by November)? Maybe it wasn’t until 10 April 1970 when Paul McCartney issued a statement to the press to say that he had left. It might have been 29 December 1974 when all the legal disputes were finally settled and the dissolution of the band was formalised.

If we can’t even agree on the date they broke up, how are we ever going to get to the bottom of the real reason of why a group of 20-somethings who, despite having already composed and recorded some of the finest songs ever written, still potentially had their best years as a group ahead of them?

At this point, some readers may be thinking, who is this idiot writing this, doesn’t he know that Yoko Ono broke up The Beatles? Well, not according to McCartney, who in a recorded conversation with Let It Be director Michael Lyndsay Hogg in 1969 said, ‘It’s going to be such an incredible comical thing like in fifty years time y’know, “They Broke up because Yoko sat on an amp”. There’s nothing wrong really’. It’s true that McCartney’s comment is far from definitive or unambiguous (you can listen to the quote in context in the video below and make you own mind up) but it does seem to strongly infer that McCartney was willing and able to accommodate Lennon and Ono’s inseparability and continue as a Beatle.

According to McCartney, the real culprit was closer to home. In Paul Du Noyer’s excellent book, Conversations with McCartney, he says, ‘There were the arguments, the business differences and all that. We were sort of coming to an end. Round about that time we made Let It Be, but because of the fraught personal relationships, the final straw that broke the camel’s back was Allen Klein coming in.”

Klein was appointed The Beatle’s manager in February 1969 against McCartney’s wishes, who would have preferred his father-in-law Lee Eastman to have had the job. A combination of Klein forcing the band to accept adding Phil Spector’s string arrangements to the otherwise stripped back Let It Be album and taking a jaw dropping 20 per cent fee from them was all too much for McCartney.

The strain on McCartney’s relationship with the other three who were in favour of Klein and his whopping cut of the profits eventually led to McCartney issuing a press statement. Accompanying the release of his first solo album McCartney, the Q&A stated among other things that his writing partnership with Lennon was over and that he had no plans to work with the other Beatles in the future. The Daily Mirror ran with the headline, ‘Paul Quits The Beatles’ laying the blame firmly at McCartney’s door, despite Lennon quitting the band a few months earlier, albeit in private.

So did Paul McCartney break up The Beatles? The truth is that major fissures had been apparent as far back as August 1968 when Ringo left during quarrels while they were recording the White Album. As he related in an interview in the Anthology documentary series,

‘I left because I felt two things: I felt I wasn’t playing great, and I also felt that the other three were really happy and I was an outsider. I went to see John…I said, ‘I’m leaving the group because I’m not playing well and I feel unloved and out of it, and you three are really close.’ And John said, ‘I thought it was you three!’ So then I went over to Paul’s … I said the same thing and Paul said, ‘I thought it was you three!’ I didn’t even bother going to George then. I said, ‘I’m going on holiday.’ I took the kids and we went to Sardinia.’

Ringo was back within a matter of weeks, greeted by a studio adorned with flowers, which was enough to reconcile him with his fellow bandmates. But fast forward five months and history nearly repeats itself, although this time the wayward Beatle is not Ringo but Harrison. As seen in Get Back, on 10 January, 1969, while the band were running through the arrangement for ‘Two Of Us’ on the soundstage at Twickenham Film studios, George announced ‘I think I’ll be…I’m leaving…the band now’. Although not recorded, Harrison reportedly told the others he would ‘See you round the clubs’ and walked out of the studio.

Although obviously shellshocked, it’s not long before John was suggesting getting Eric Clapton in as a replacement and ruminating about Harrison, saying, ‘I’m not sure whether I do want him’, hardly the sign of a stable and happy group situation. After a band meeting at Ringo’s house, Harrison agreed to return if the idea for a big live show, which the filmed rehearsals at Twickenham were moving towards, was dropped and rehearsals were relocated to the basement studio at Apple HQ in Saville Row, both of which the other band members acceded to. That Harrison felt the need to dramatically quit and for his return to be dependent on demands and ultimatums doesn’t exactly scream happy campers. With the band on such shaky ground, it was inevitable that something or someone would soon turn out to be the final straw and that just happened to be Klein.

But the real reason The Beatles broke up was because they had to. They were like the universe, ever expanding. The moment when John, Paul, George and Ringo were first in a room together was the big bang, a release of creative energy that would eventually pull them apart. To mix metaphors, a Beatles year is the human equivalent of a dog year; what they experienced and achieved in 12 months would take most mere mortal a decade. They were maturing and transforming at an astonishing rate and they only way they could realise their full potential was separately, not together. As Harrison noted in Anthology, The Beatles ‘gave us the vehicle to be able to do so much’ but ‘it got to the point when it was stifling us, there was too much restriction. It had to self destruct’.

Maybe the ideal outcome was not a permanent disbandment, but a hiatus every so often so that they could let off steam with solo projects and then come back together to do more Beatles. But, arguably, The Beatles as a unified band ceased to truly exist after Revolver. After that, they were four individuals clinging on to the idea of The Beatles but spinning further away from the reality of what The Beatles had been; every new release pointing towards a future where The Beatles would no longer exist. In their hearts, The Beatles knew better than anyone that it was time to let it be.

Eyes of The Storm is a magical, unmissable exhibition of 250 never before seen backstage pictures taken by Paul McCartney between November 1963 and February 1964. In an introduction to the exhibition, McCartney says that, ‘I’m not setting out to be seen as a master photographer, more an occasional photographer who happened to be in the right place at the right time’. Even if McCartney isn’t technically brilliant (although to my relatively untrained, photography ‘O’ level grade C eyes, the shots appear to be high quality stuff) he made the most of his unique position to capture his fellow Beatles and entourage on film like no one else could ever do.

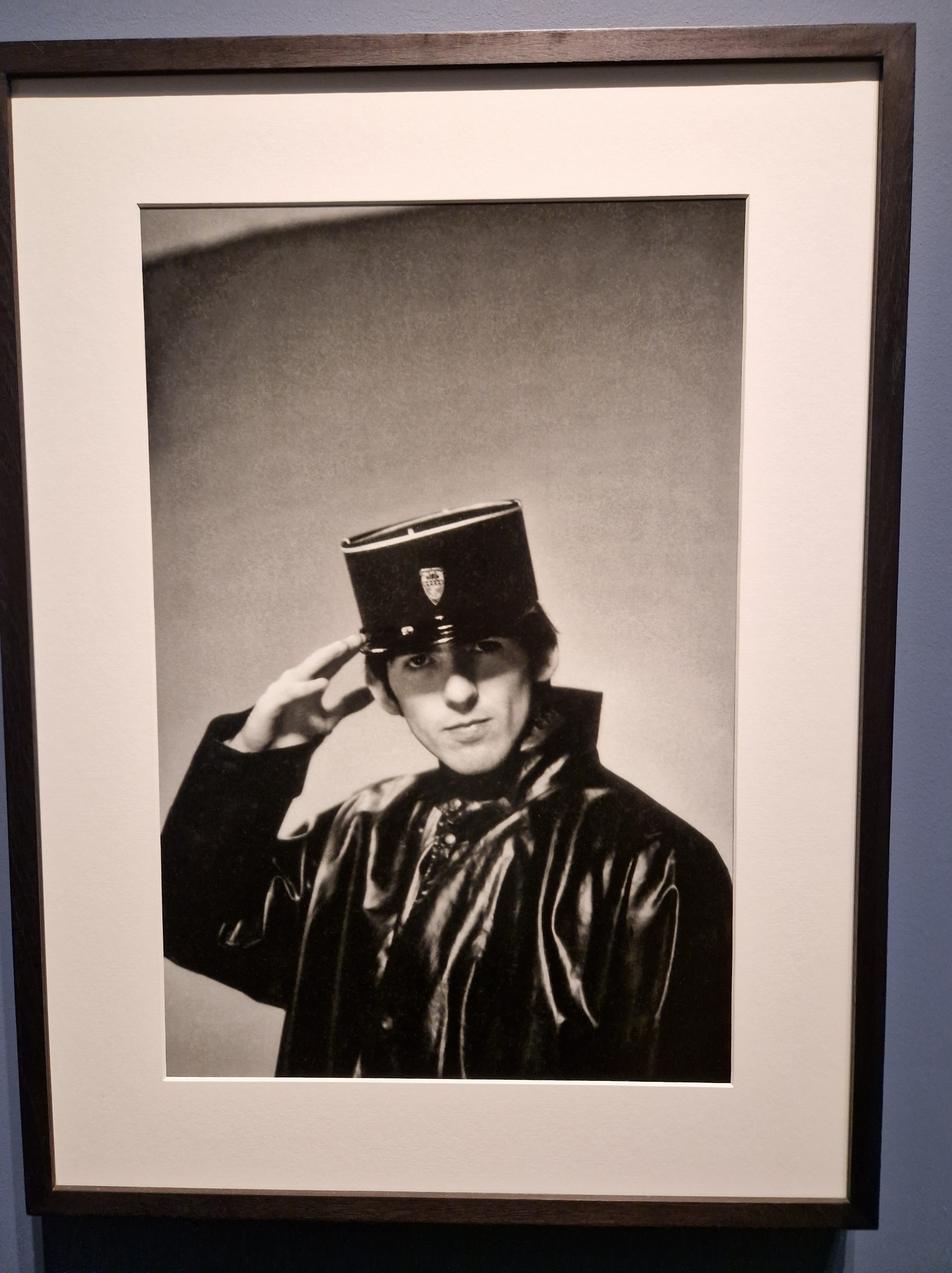

There is an unequalled intimacy to McCartney’s candid portraits of Lennon, Harrison and Starr that is just beguiling. It’s as though the camera doesn’t exist; there’s no barrier between McCartney and his subjects who are seemingly captured at their most relaxed. His shots of Mal Evans and Brian Epstein are also wonderful. All of them appear in the first part of the exhibition which documents the band’s 1963 autumn UK tour, the filming of an episode of Juke Box Jury and It’s the Beatles for the BBC in Liverpool, The Beatles Christmas Show at the Astoria in Finsbury Park and their London Palladium shows in January 1964. The photographs of The Beatles hectic trip to Paris, also in January 1964 also contains some great images including Harrison dressed as a gendarme.

The exhibition is less successful when The Beatles make their first visit to America and McCartney turns his attention away from the band and towards ‘airport workers, the police and the press photographers’. While it’s interesting to get a inside-out view of Beatlemania, there are a few too many mundane snapshots. Things pick up when McCartney arrives in Miami and starts shooting in colour (there’s a specially commissioned film with a new score by McCartney playing in the Miami room which adds interest) although there is more than a hint of holiday snap to many of the pictures.

Despite these minor shortcomings, Eyes of the Storm is an absolute joy. I found myself grinning like an idiot for most of the hour I spent in the gallery. I would allow at least that to see the exhibition and more like 90 minutes to do it proper justice. The galleries were quite packed on a late Thursday afternoon so it’s probably worth going early morning if you can, I imagine this will be a popular show and rightly so. Any Beatles fan will absolutely love it.

Eyes of the Storm is on at the National Portrait Gallery until 1 October 2023. Click here for more information.

The song ‘suite’ plays a major role in The Beatles canon, both band and solo eras. For many, it the form will forever be associated with McCartney and Wings. From ‘Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey’ to ‘Medley: Hold Me Tight/Lazy Dynamite/Hands Of Love/Power Cut’ to ‘After The Ball/Million Miles’ and ‘Winter Rose/Love Awake’ or the pocket symphonies of ‘The Back Seat Of My Car’ and ‘Band On The Run’.

All of that stems from the fragmentary glory that is Side Two of 1969’s Abbey Road, the musical definition of a whole that is greater than a sum of its parts. It’s arguably the aural summit of The Beatles’ recorded work. However, the finale of the album almost called ‘Everest‘ was derided by John Lennon as ‘unfinished songs all stuck together. Everybody praises the album so much, but none of the songs had anything to do with each other, no thread at all, only the fact that we stuck them together‘ (John Lennon Playboy interview with David Sheff, September 1980 (published January 1981)). Lennon’s criticism is harsh, but there is truth in it. While ‘Abbey Road Medley’ ( Side Two of Abbey Road is colloquially known as the ‘Abbey Road Medley’, however, the 2019 box-set reissue also refers to it as ‘The Long One’) is a delight, befitting the end of a decade and the band that defined it, there is an earlier near-perfect track sequence in The Beatles’ canon.

Side Four of The White Album is often overlooked and even ignored as the ‘weird’ side; evidence that the 1968 thirty-track behemoth should’ve been a two-sided LP. But it might just be the best example of a song suite in popular music. Individually, ‘Revolution 1′, ‘Honey Pie’, ‘Savoy Truffle’, ‘Cry Baby Cry’, ‘Revolution 9’, ‘Good Night’ are unlikely to make anyone’s Friday night playlist. If you met someone at a party who said that any one of them was their favourite Beatles track you’d make your excuses and head to the bar.

One might even go as far to say that not one of the tracks stands out on The White Album. The popular verdict: ‘Revolution 1’ is a less-exciting cousin to the raucous, electrifying B-Side to ‘Hey Jude’. ‘Honey Pie’ personifies (in name and substance) the sickly-sweet nadir of McCartney’s pastiche and ‘Savoy Truffle’ is another forgettable ‘Harrisong‘, meaninglessly listing the contents of a chocolate box and warning against the perils of tooth decay. ‘Cry Baby Cry’ is a glorified lullaby based on an advertisement, a continuation of post-Rubber Soul Lennon laziness, ‘Revolution 9’ is a mess of noise, a waste of vinyl space at 8 minutes, 22 seconds. Ending the album with ‘Good Night’, a Ringo vocal is a bad move to say the least, exacerbated by Disney tremolo strings and saccharin lyrics.

Side Four of The White Album, ‘You can count me out (in)’. Right?

Wrong.

A Doll’s House

1968’s The Beatles (whilst this is the official album title, it quickly became known as The White Album for its minimalist cover) was almost called something very different . Had it not been for British psychedelic group Family’s debut LP Music In A Doll’s House released in July of the same year, the Beatles’ only double was slated to be ‘A Doll’s House‘.

Imagine that. A creepy Victorian miniature mansion with 30 rooms, one for each song. Each behind an auspicious door with which, upon opening, you might be met with anything from a dose of pastiche surf rock (‘Back In The USSR’), a game of self-referential Beatles Cluedo (‘Glass Onion’), a paean to mating primates with one of the most underrated rock vocals of all time (‘Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?’), a song about a sheepdog (‘Martha My Dear’), a blackbird (‘Blackbird’) or a Raccoon (‘Rocky Raccoon’), a dystopian warning à la Orwell (‘Piggies’), an anti-hunting anthem? (‘The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill’), a slagging off of Sir Walter Raleigh (‘I’m So Tired’), a slagging off of the Maharishi (‘Sexy Sadie’), a slagging off of ‘you all‘ and the invention of 1970s FM radio rock (‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’), the world’s first heavy metal song (‘Helter Skelter’), a bassline played with the mouth (‘I Will’), a Psych/hard rock/gun magazine Doo Wop (‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’), a song for anyone with a birthday this year (‘Birthday’), Ringo’s songwriting debut country groove (‘Don’t Pass Me By’), a cowbell maybe even too prominent for Christopher Walken in the Saturday Night Live sketch ‘More Cowbell’ which aired on 8th April 2000 (‘Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except For Me And My Monkey’), a blues dirtier than a Woodstock puddle (‘Yer Blues’), potentially androgynous reggae (‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’), an attempt to coax Mia Farrow’s sister from a hut (‘Dear Prudence’), the musical and spiritual meeting of the two great loves of John’s life (‘Julia’), an acidic glimpse of mantra madness (‘Wild Honey Pie’), pre-‘Country Dreamer’, country-dreamer-Paul (‘Mother Nature’s Son’) or drums so distant and heavy they sound like they could’ve been recorded in the Himalayas six months earlier, the sound only just reaching you now (‘Long, Long, Long’).

After the pop side (Side One), the folk side (Side Two) and the rock side (Side Three), Side Four is ‘The Doll’s House Side‘. It should be noted that what follows is not a proclamation that Side Four of The White Album is a predetermined concept or even, on a song by song basis, necessarily how The Beatles intended to convey meaning through its contents. However, it is an interesting way in which you can listen to it and, more importantly, it’s a lot of fun; a manual for a new way to try the songs you may have underestimated by the band you thought you definitely hadn’t.

A childlike revolution

Revolution 1

Recording sessions for The White Album began in EMI Studio Two at Abbey Road on Thursday 30th May, 1968. Having recorded the extensive Esher Demos at George’s Surrey bungalow, Kinfauns, the boys had over forty songs from which to build the official follow-up LP to Sgt. Pepper (Magical Mystery Tour was only released as an EP in the UK. Interestingly, 1968 is the first instance since 1963’s Please Please Me where The Beatles had more material than was required to fill an album and the only time where all of that surplus was original material). ‘Revolution’ was selected as the first of the new batch to be recorded and the work done on this day gives us two of the songs on Side Four of the eventual LP (Take 20 produced ‘Revolution 1’ and its extended outro provided the structure of ‘Revolution 9’).

The White Album is inextricably linked with The Beatles’ pilgrimage to Rishikesh, beginning in February 1968. Although reference to the Indian experience justifies the acoustic timbre of a significant portion of the album, it is perhaps just as prudent to consider the album in the context of the year of its creation which, like 1967, is a year in which its music is difficult to separate from its events.

By late ’67 it was becoming clear that the hippie utopia wouldn’t materialise on either side of the Atlantic. The Haight-Ashbury had descended into “ghastly drop-outs, bums and spotty youths, all out of their brains” (George Harrison’s comment on witnessing San Francisco in 1967, included in Derek Taylor’s memoir ‘As Time Goes By’ (1973)). US death tolls in Vietnam were at their highest in 1967-1968 at more than 28,000. On 17th March 1968, approximately 25,000 people gathered outside the US Embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square to protest the US involvement in Vietnam, resulting in riots. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated on 4th April in Memphis and Robert Kennedy on 6th June – a week into The White Album sessions – in Los Angeles.

It is, therefore, hard to ignore the notion that, in beginning work on their new album, The Beatles were following past practice and reacting to the world outside Abbey Road, setting ‘Revolution’ and its subject matter as The White Album‘s manifesto.

Whether discovering The Beatles in real time or later you were likely already familiar with another version of the song; the distorted guitar and screams version which backed ‘Hey Jude’ as the first Beatles’ release on the Apple label (26th August 1968). ‘Revolution 1’ was, and to a degree still is, therefore, a surprise. It has broadly the same arrangement as the B-Side but is much slower, less electric and with an almost comical doo-wop backing.

Whereas the single version ‘Revolution’ embodies the idealised uprising from the perspective of its subscribers and participants (perhaps the Grosvenor Square crowds) ‘Revolution 1’ is more like a middle-aged, bowler-hatted Londoner, let’s call him Harold, walking through those 1968 scenes. Passively passing through Ladbroke Grove, he is sympathetic to the cause but feels the need to point out why it is so easily undermined by those so inclined with the lines ‘if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow’ and ‘if you want money for people with minds that hate, all I can tell you is brother you’ll have to wait’.

The protagonist does not necessarily feel part of the ‘Establishment’, but his age lends itself more readily to the established order than to subversion of it. This generational gap creates an unbreakable apathy in the older generation, in which its flippant treatment of the younger generation and its dogmatic belief that to ‘change the world’ is an impossibility is acutely distilled in Lennon’s sarcastic vocal delivery: ‘we’re all doing what we can’.

Honey Pie

‘Honey Pie’ is disadvantaged by its place in the The White Album track listing. Firstly, after three-and-a-bit sides of largely unusual music, a listener may be fatigued. Secondly, we’ve already heard ‘Wild Honey Pie’. That either means we’re intrigued by what a similarly-named song has to offer (not a great deal as it turns out) or, if you hated ‘Wild Honey Pie’, ‘Honey Pie’ is already tarred with the same brush. Thirdly, ‘Honey Pie’ naturally falls within the McCartney music hall catalogue of which this album already exhibits a superior representative in ‘Martha My Dear’.

But maybe, just maybe, ‘Honey Pie’ isn’t a music hall pastiche. Harold arrives home. He’s off the streets of a crumbling London and into his sanctuary where, if he likes, nothing ever changes. He pours himself a cognac and places the gramophone needle on his favourite 78; the sound of the 1940s, his golden generation. He dreams of Hollywood and romance; the song’s heroine evokes the great loves of his youth before he settled down into a settled job and a settled life. ‘Honey Pie’ is an exploration of his delusional apathy and selective ignorance of the reality of things. In providing a stark contrast to the breakdown of the psychedelic generation’s attempts to change the world, it represents the very people best-placed to assist yet whose only act was to turn their backs and turn up their radios to drown-out the sound of a world about to erupt outside the four walls of their homes.

Savoy Truffle

The compressed horns of ‘Savoy Truffle’ lay a fanfare foundation for the entry of the family’s children into the front parlour with their mother holding a new baby. They’re excited to see their father, home from another very important day in the very big city making the world go round. They’re clutching at boxes of chocolates and grinning from ear to ear. The Mackintosh’s ‘Good News’ varieties listed in the lyrics contrast with the bad news about to unfold outside. Shinily-wrapped in a tooth-decay warning, Harrison’s metaphor is dual-purpose for the loss of the innocence of childhood by adopting those ‘adult’ ideas of security, self-preservation and greed and, with it, the decay of progressive society. An arguable theme of the album is the notion that once such innocence is lost, it is irretrievable: ‘You might not feel it now, but when the pain cuts through you’re going to know and how the sweat is going to fill your head, when it becomes too much you shout aloud’, sings George in a sentiment that goes beyond a mere call for a Clapton root canal (the genesis of the song was friend (and White Album contributor) Eric Clapton’s love of chocolates).

Cry Baby Cry

Father sings a lullaby to his family, ‘cry baby cry, make your mother sigh’. The man of the house is happy to admire his family at a distance but without adopting direct responsibility; they are one of his marks on the world (‘the children of the King’) and it is enough, to him, that he graces them with his presence. His wife is ‘old enough to know better,’ supposing that age equals wisdom, a view that the songwriting is questioning here. The enemy to progress is the established order, the staid way of thinking, risk-averse sensibilities and the only burning desire, seemingly, a one to ‘grow up’.

The characters in ‘Cry Baby Cry’ are obvious symbols of this established order. The Duke is ‘having problems with a message at the local bird and bee’. Perhaps he is physically barricaded in his local pub by active participants in the peaceful revolution. Perhaps the childlike suggestion of the ‘birds and the bees’ presents him as emotionally barricaded from showing his wife the love she deserves. She, the Duchess, seems to be elsewhere, maybe invited to the family home for tea after the children go to bed. ‘Cry Baby Cry’ is The Last Supper for the establishment while the revolution rages on the other side of the draped windows.

The hidden track between ‘Cry Baby Cry’ and ‘Revolution 9’ harnesses the ethereality of the former, souring in its fading notes toward the apocalyptic feel of the latter. ‘Can you take me back where I came from?’ sings Paul with reverberant acoustic guitar accompaniment. The final verse of its parent track describes ‘a séance in the dark with voices put on specially by the children for a lark’. Is this, the child track, the voice of one of those children larking about? Or is it the voice of a ghost trapped in the Ouija board and summoned up during the séance? The repeated one-line lyric could be heard as a plea by the adults in the room to revert to the innocence and security of their own childhood, but they know too much and find themselves helpless. They are the dolls in a Doll’s House.

Revolution 9

‘Revolution 9”s foray into musique concrète is the sound of the revolution itself. John Lennon has said as much: that the song is ‘an unconscious picture of what I actually think will happen when it happens; just like a drawing of a revolution’. The Lennon/Harrison collaboration is possibly better-described as a Lennon/Harrison/Ono collaboration, significantly influenced by an absent Beatle first-interested in avant garde experimentation and the use of tape loops, Paul. In any event, the supposedly random collection of sounds throws up some interesting ideas.

The ‘Number 9, Number 9’ refrain is not reminding us Paul is dead. It is the Doll’s House gramophone sticking; the party is almost over and the world outside is falling apart. ‘Revolution 9’ evokes the disconcertion of a semi-dream state, its split-screen narrative flicking between what is going on inside and outside of the Doll’s House. The introductory exchange between George Martin and Alistair Taylor apologising for not buying a bottle of claret, followed by the exclamation of ‘cheeky bitch’ makes the listener feel they’re eavesdropping on a middle-class conversation in the [pineapple] heart of Dinner Party Society.

The crazed female laughter is the Duchess from the previous song, ‘always smiling and arriving late for tea’. The discussions of the ‘price of grain in Hertfordshire’ and ‘financial imbalance’ are the gentlemen discussing matters of a fiscal nature over a cigar while the baby cries in the corner for its mother’s attention. Outside, the prophecies of ‘Revolution 1’ are coming true with riots and gunshots and cries of “Right, Right”. George’s repeated ‘El Dorado’ is foreshadowing the fall of the empire around the Doll’s House next to his sombre double refrain ‘Who was to know?’ suggesting a tragic meaningless to all this violence.

As the sound collage reaches its chanting climax, its most famous line, spoken by Yoko, ‘if you become naked’ is confirmation that the regression to a childlike state is the answer – the true revolution is not political, economic or violent but is to reject baseless ‘adult’ ideas. The dream isn’t over, it’s just a different dream to what we thought was the answer in 1967.

Jonathan Gould wrote that ‘Revolution 9’ is ‘an embarrassment that stands like a black hole at the end of the White Album’. But it isn’t at the end of The White Album and the track that closes out the LP is far from a black hole.

Good Night

No other song from the Esher Demos would be a more appropriate finale to this strange and wonderful cabinet of curiosities and, sometimes, there’s no other song in the world that I’d rather listen to than ‘Good Night’. The comfort of Ringo’s voice cascades from the record like a warmed blanket unfurling, inviting the listener to feel like a child being tucked-in for a sound night’s sleep by its singer. And that is why it’s perfect. None of the other Beatles could have sung it convincingly, yet Ringo is earnest. ‘Good Night’ is the foil to ‘Revolution 9’. In the same way that the gravity of Revolver‘s closer is tempered by its comic title, The White Album‘s final song sweeps away any pretension left hanging after ‘Revolution 9’, yet simultaneously progresses the apparent theme of Side Four, resolving it in the only way The Beatles knew how, with positivity. Within the safety of the child mind, the regression from the chaos of the adult world is complete and maybe it is ‘gonna be alright’.

Take this, may it serve you well

The resurgence in popularity of the vinyl record is encouraging for the preservation of the ‘album’ as an art form. If artists are to write and record successful ‘albums’, attention must be paid to track sequencing and how a side of vinyl flows, develops, balances light and shade, maintains interest and leaves a lasting impression. Whereas Side Two of Abbey Road is a masterclass in sonic knitting, Side Four of The White Album is a thematic opera: A Doll’s House. If you’re striving for a new way to listen to The Beatles, I invite you to revisit Side Four and see what you think it’s all about. After all, it’s all in the mind you know.

Written by Jordan Frazer. Follow him on Twitter at @TheStylusMethod and find out more about the band at Bandcamp

On 30th May 2022, I walked up the fabled steps of Abbey Road Studios, guitar in hand, heart in mouth. I was there to record with my band, The Stylus Method, for our second album, The Imaginary Costume Party. Anyone who has made the pilgrimage to St. John’s Wood will be familiar with the magic feeling the place conjures, despite its understated external appearance and sleepy surroundings. Entering the rabbit-warren of connecting corridors, stairways and secret passages adorned with the faces of musical and cinematic greats, I felt honoured to be contributing to the rich seam of sound recorded here. I hoped to mine some of those jewels during my own musical journey there.

Mary McCartney’s new documentary If These Walls Could Sing, celebrating the 90th anniversary of Abbey Road Studios, re-creates that feeling in its opening sequence. As narrator, she even makes the same point: ‘every time I walk through these corridors it feels magical’. Some flashing glimpses of a young George Harrison with his 12-string Rickenbacker and Wings-era Paul and Linda standing on Studio 2’s parquet floor help to set the scene for what follows.

90 minutes for 90 years is barely enough time to scratch the surface and it must have been a difficult task to narrow down the shortlist of contributors. However, the stories and interviews selected are rather hard to argue with. The film begins in 1931 with the black and white genesis of Abbey Road, its inaugural recording/performance of Sir Edward Elgar conducting a live orchestra through his ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, cut straight to a 78rpm disc. McCartney then traces the transition from classical to pop and back again. Cliff & The Shadows, Cilla Black, Gerry Marsden, Pink Floyd, Fela Kuti, Nile Rodgers, Kate Bush, Oasis and Celeste are bookended by performances of Elgar’s ‘Cello Concerto in E minor, Op.85′ by Jacqueline du Pré in 1967 and Sheku Kanneh-Mason in 2022, demonstrating the expanse of genres to flourish at Abbey Road, still the place to be to record the world’s greatest music.

Sir Elton John and Jimmy Page recall their days as young session players. The reverence with which they talk of Abbey Road and the musicians with whom they worked in those days is genuinely humbling and shows the power of music in bringing together and inspiring a community of like-minded creatives.

Perhaps the most interesting section of the film is the studios’ survival story, through the drought of bookings in the late 1970s & early 1980s when Studio 1 was relegated to a staff badminton court (and nearly converted into a car park) before being rescued by the tireless work of its staff and a renaissance in film music. Legendary composer John Williams of Star Wars fame provides some delightful insights, including his memories of the studio canteen (which I can confirm from experience serves extremely good roast potatoes). Rather perfectly, the London premiere of If These Walls Could Sing was the first ever to be hosted in Studio 1.

While the coverage of the Fabs’ time at Abbey Road is substantial, the film’s focus is not on the Beatles themselves or their music; it’s on the people at Abbey Road who made it happen (and continue to reinvent it) or, as Paul describes them, the ‘really cool boffins’. From the great George Martin – Ringo putting it eloquently, that ‘George was incredible and we were buskers’ – the tireless work of Ken Townsend, starting out as a trainee engineer in 1950 to retiring as studio chairman in 1995, faithful veteran technician Lester Smith and insights from current studio manager Colette Barber, the commitment to Abbey Road transcends simply what these people do for work; it is love.

It’s always spine-tingling to hear the surviving Beatles talk about ‘The Beatles’ and there’s plenty of that to enjoy. Paul seems genuinely excited to be there, in Studio 2, giving us a rollicking rendition of ‘Lady Madonna’ on the Mrs Mills piano and proclaiming the essence of what Abbey Road meant to the 1960s cultural revolution: ‘here you were in London, which was on fire’.

There are also some choice quotes (and drumming) from Ringo, who is looking fabulous, revealing his favourite song is ‘Yer Blues’. On Paul, he says, ‘if it hadn’t’ve been for him we’d have made like three albums’ and, on The Beatles, ‘it worked out pretty well for us’. You could say that Ringo.

The film includes archive clips we’ve all seen before, like the December 1966 interviews of the newly moustachioed Fabs arriving to work on the Sgt. Pepper sessions or the discussion of John’s ethereal vocal in ‘A Day In The Life’ (from the Anthology series). However, the words from Giles Martin are rather touching, picking up where his dad left off in similar no-nonsense terms that ‘it’s the four of them in a room making a sound together’ which is, perhaps, the most valuable asset of any great recording studio: a space in which people can create music together.

What Mary McCartney does with this film is to illustrate the cultural (or countercultural) significance of Abbey Road. A contemporaneous poetic critique of Sgt. Pepper from Allen Ginsberg gives credence to Roger Waters’ comment that this music gave musicians ‘permission to write songs about real things’ and ‘the courage to accept your feelings’. For, in this building, an entire artistic movement was born, not just a musical one but something much greater and enduring, spanning continents and lasting generations.

In that pursuit, we’re treated to some lovely archive clips such as Paul conducting the orchestra for ‘A Day In The Life’ (complete with clown noses and bald wigs) and a voice-over from George Harrison on the ‘All You Need Is Love’ filmed performance in Studio 1, its technicolour contrasting with the earlier Elgar scene in the same room. In one of the film’s finest moments, we’re shown a clip of Blackbird from the White Album sessions in 1968 (the year before Mary was born) kept in time by the tapping of Paul’s yellow and red shoes. Then, 56 years later, he plays a snippet of the song for his daughter’s camera. Reference to the unstructured Get Back/Let It Be project and a return to Abbey Road for the album of the same name provides a clever dramatic irony for the 2023 audience. The chaos of the former rectified by the latter which, in turn, now officially gives its name to the studios themselves.

Shown working on new music in Studio 3, Nile Rodgers observes that ‘so many massive rock and roll records were made here, people don’t believe that it was just done by accident’. The inherent superstition of musicians will mean that we’ll never know. However, despite the ‘smell of fear’ one might experience upon entering this hallowed ground to commit recorded sound to the history books, If These Walls Could Sing reminds us that Abbey Road is not a pretentious place.

The mark of a good documentary, Mary McCartney rarely emerges from behind the camera, instead seeking to capture the magic of Abbey Road which, for all its history and legend, is not just surviving on past glories, in fact, quite the opposite. It’s more than the name, the zebra crossing or the album cover. This is the most unlikely underdog story of what is still a working studio, and probably the best one in the world.

The studio hasn’t been made over or even tidied up for the documentary. Equipment isn’t pushed to one side to make room for better camera angles. The interviews in Studio 2, particularly those with Paul and Ringo, show cables, baffles and ‘sleeping bag’ dampers in the background and, from the door to the echo chamber to the stairs and god-like control room window, it looks just the same as it did in 1963 for the Please Please Me full-day album session culminating in, as Giles Martin puts it, ‘John’s ripped vocal’ in ‘Twist And Shout’.

For a British institution like Abbey Road, it’s rather frustrating that our American friends were able to watch If These Walls Could Sing two weeks before us, but it was well worth the wait (and a Disney subscription). Fittingly, this film stresses the eccentric Britishness of it all. Noel Gallagher describes the spirituality of the place akin to record shops, pubs, and football stadiums, while Giles Martin analogises that you’re never meant to clean out a teapot: ‘you walk down into Studio 2 and you feel as though the walls are saturated with great music’.

Why is Abbey Road still the greatest place on Earth to record? For all its mysticism, maybe the simple answer lies in the following two quotes:

– ‘People want to come here, they want the sound of Abbey Road’ (Sir Elton John).

– ‘All the microphones work’ (Sir Paul McCartney) – something which will resonate with musicians everywhere who have ever paid for studio time.

The Beatles Handbook rating: 4 stars

Review written by Jordan Frazer. Follow him on Twitter at @TheStylusMethod and find out more about the band at Bandcamp

`1965: Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts

For all their distinct personalities, the four Beatles were effectively a gestalt entity. This was one of the reasons why they so perfectly represented Eros, or the Freudian drive to lose your limited self and become part of something larger.

In the decades after the band split, much debate occurred about why they were so special, with the assumption being that the answer must lie with one of the four. In the seventies and eighties, many rock critics took the view that John Lennon was the special ingredient which explained the extraordinary impact of the Beatles. Thinking like this was entirely in keeping with the individualism of the second half of the twentieth century. But as a framework, individualism was always too limited a perspective to understand something as interesting as the Beatles. It was the combination of those four personalities which made the Beatles greater than the sum of their parts. They were, in occult terms, a combination of the four alchemical elements. Ringo was earth, John was fire, Paul was air and George was water. Combined, they produced the fifth, transcendent element: spirit. Or alternatively, Ringo had a big nose, George had big ears, Paul had big eyes and John was always a big mouth. As individuals these attributes may be unfortunate, but when they are combined you get the face of a giant.

And then Paul McCartney wrote ‘Yesterday’.

This is, of course, one of the most covered songs in history. The melody famously came to Cartney fully formed during a dream, a gift from his subconscious that would change his life forever. It elevated him from being part of his ‘good little rock ‘n’ roll band’ to becoming the author of the front page of the twentieth century’s songbook. Even half a century after it was written, it’s impossible to grow up in the West and not know this song. It hinted at the scale of the new territory that the Beatles would now occupy. But it also hinted at the cost.

Before ‘Yesterday’, the Beatles were a unit. Lennon and McCartney had previously written songs alone, without the insights and finishing touches of their partner. But this was the first solo song that didn’t need the other three Beatles. Instead, it was recorded in two takes with Paul alone, playing acoustic guitar and singing, and George Martin added a string quartet three days later. On the same day that McCartney recorded Yesterday’, the full band also recorded two more of Paul’s songs, the larynx shredding rocker ‘I’m Down’ and the acoustic folk rock ‘I’ve Just Seen a Face’ – an example not just of the phenomenal work rate that the band operated at, but the variety of styles of both singing and songwriting that McCartney was capable of.

The solo nature of the song clearly troubled the band; here was a situation that they had never had to deal with before. It is striking that, uncomfortable with such a solo effort being credited to the Beatles, they didn’t release the song as a single in the UK. It’s hard to imagine any other band writing a song as strong and commercial as ‘Yesterday’, then only using it as filler on the second side of a film soundtrack album.

What ‘Yesterday’ showed was that new horizons for the band’s music were imaginable. It was not that they had plateaued and were on the way down, it was more that they had barely started. If they were to reach those new artistic peaks it would require the four Beatles to grow and evolve as individuals. They could not remain loveable mop-tops forever. But if the four of them were to change in unexpected and unpredictable ways, then how could they be expected to fit together so neatly into the perfect unit that won the hearts of the world? The future was unparalleled creative growth, yet as the melancholic mood of ‘Yesterday’ realised, it would come at a cost.

‘Yesterday’ is a song about realising that something special has changed and wishing to go back in time to how things used to be. The Beatles were going to mature into four extraordinary individuals who would offer the world so much more than the pre-‘Yesterday’ Fab Four. For all four musicians, their greatest work was ahead of them. But there is a reason why many children fear growing up. The arrival of the future, after all, must mean the death of the past. To evolve and fulfil their potential would mean allowing fractures to grow in the best gang imaginable.

LOVE AND LET DIE by John Higgs published by W&N available in Hardback, eBook and audio £22

Buy this book: Love and Let Die by John Higgs

Read a Q&A with John Higgs

Coming soon

Read the review

Coming soon

Most songwriters would give their right arm for just one of the melodies, riffs or chord sequences on Revolver. The playing is terrific too. From the looping bass, taut guitar stabs and crisp drumming of the opening ‘Taxman’, to the hallucinatory ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ with that legendary, defining Ringo drum pattern, The Beatles sound like the tightest band on the planet. And they don’t just hit the back of the net with rock, pop and psychedelia; whatever they turn their hand to on the album is pure gold, from the heart-breaking pathos of ‘Eleanor Rigby’ with its haunting double string quartet arrangement, to the achingly tender ‘Here, There and Everywhere’, arguably McCartney’s most beautiful love song. With every track a banger (and no, I’m not excluding ‘Yellow Submarine’ which has the hookiest chorus ever written), it’s unquestionably the highpoint of The Beatles recording career. An awe-inspiring achievement, especially when you consider it was released only eight months after Rubber Soul and that many of the tracks wouldn’t even make a top 20 of The Beatles best known songs.

Beatles Handbook rating: 5 Stars

Essential tracks

Eleanor Rigby

Here, There and Everywhere

And Your Bird Can Sing

Got To Get You Into My Life

Tomorrow Never Knows

Buy this album: Revolver

For any other band, Help! would be a greatest hits album. But because this is The Beatles, it’s just another shift in the mop tops’ factory of greatness. With what must be the most impactful beginning of any pop album, ‘Help!’ makes for a direct, startling opening statement, vulnerable and yet uplifting as though by simply making the request, Lennon has made himself feel better. With only one track tipping the three minute mark (Ticket To Ride at a hardly epic 3m9s), the band rattle though 14 perfect slices of guitar pop. Every track is a cracker, including the Ringo-sung ‘Act Naturally’. As astonishingly excellent as the film it soundtracks is appallingly bad.

Beatles Handbook rating: 5 Stars

Essential tracks

Help!

The Night Before

You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away

You’re Going to Lose That Girl

Ticket To Ride

Buy this album: Help!

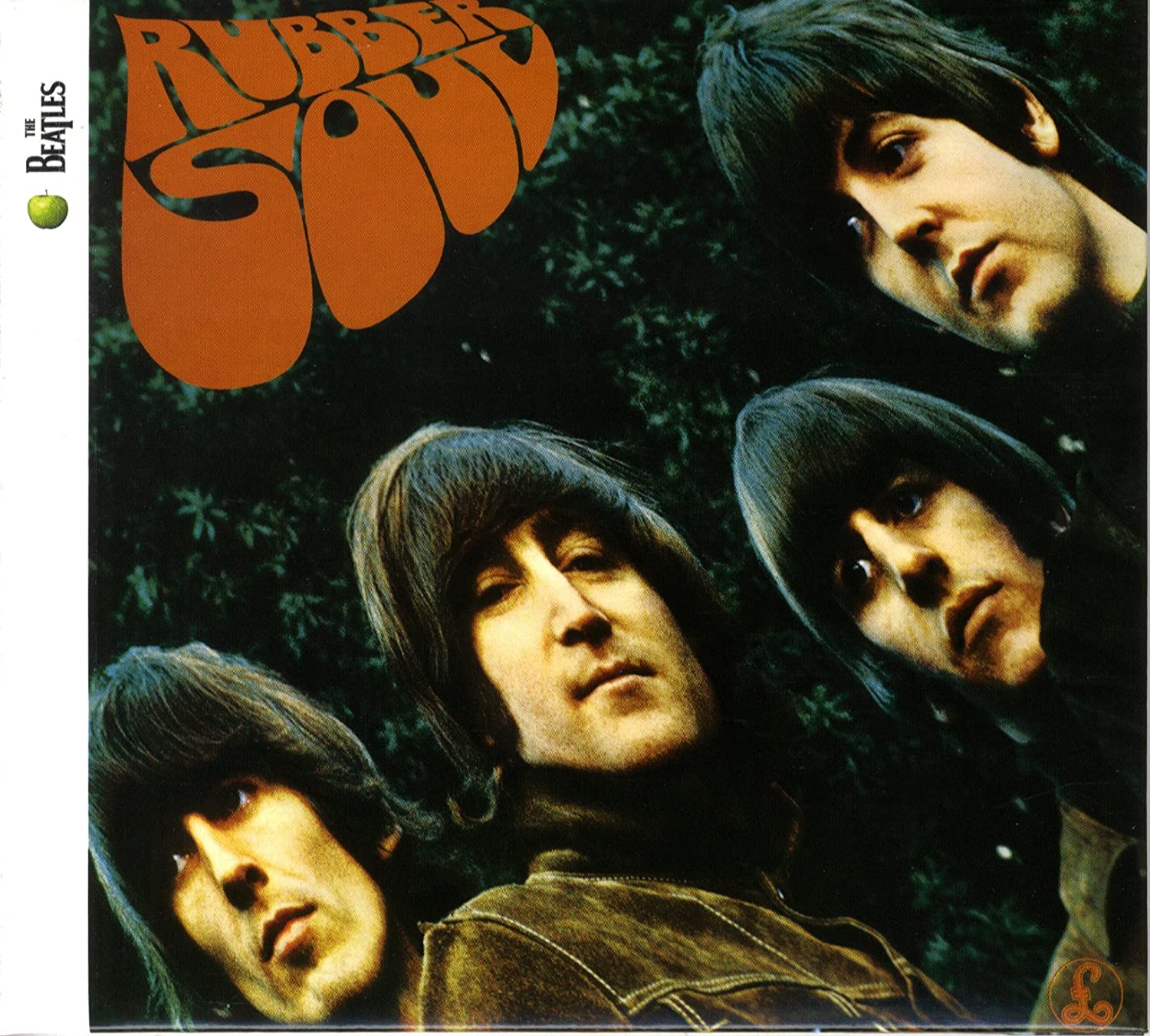

It’s amazing what you can do with some tight guitar riffs, even tighter vocal harmonies, passing piano chords and a killer hook line. ‘Beep, beep, beep, yeah’ indeed. It’s incredible to think that, a little more than two years earlier, the same four lads were banging, thrashing and crooning their way through a disparate rag bag of rudimentary rockers and schmaltzy ballads. And ‘Drive My Car’ is just one of any number of sophisticated, mature, memorable and melodic songs on what isn’t even their best album. It may be a music mag all-time-best-list staple but it can’t quite keep pace in terms of quality with Help! or Revolver, but make no mistake, this is a band close to the very height of their powers sounding both assured, thrilling and moving by turns.

Beatles Handbook rating: 4 Stars

Essential tracks

Drive My Car

Norwegian Wood

Nowhere Man

The Word

Girl

I’m Looking Through You

In My Life

Buy this album: Rubber Soul

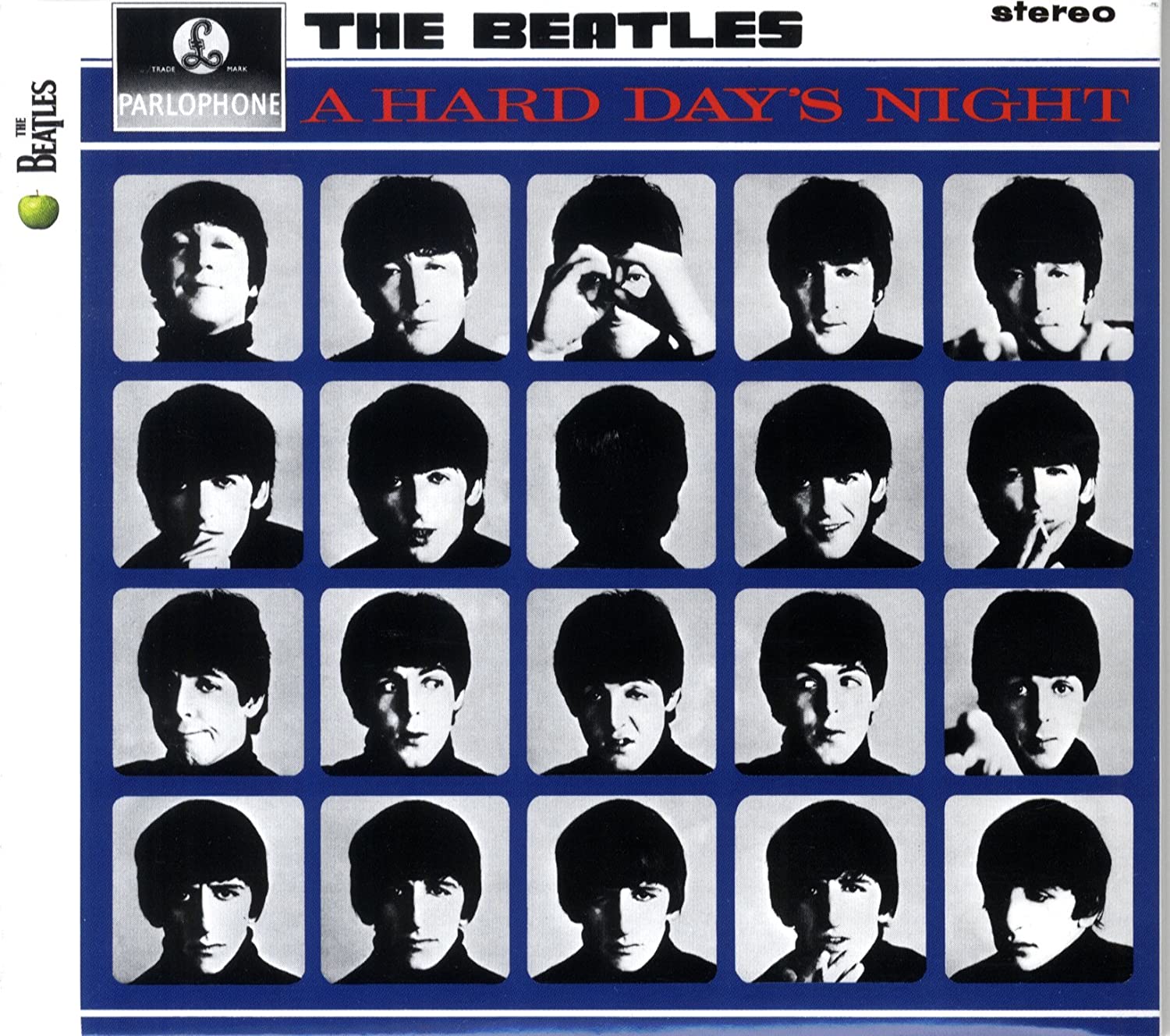

As Luke Haines recently noted in his column in Record Collector, “the opening chord of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’… singlehandedly seemed to usher in a new era”. It certainly ushered in a new era for the mop tops themselves with what might be considered by contemporary listeners as their first ‘proper’ album. Most of the Hamburg hard edges have been sanded off and chugging rock’n’roll for the most part replaced by sophisticated song writing with ace melodies and harmonies. Lennon dominates, taking lead vocals on nine out of the thirteen tracks and, according to beatlesarchive.net, writing ten, but McCartney still manages to make a big impression with his three contributions; the hauntingly beautiful ‘And I Love Her’ (the signature opening guitar motive courtesy of Harrison), the instantly catchy ‘Things We Said Today’ and of course the timeless classic ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’. Harrison is given ‘I’m Happy Just To Dance With You’ to sing, one of the weaker numbers that wouldn’t have been out of place on Please Please Me or With The Beatles but it’s still a pleasant enough sub-two minute listen. A great album that soundtracks the band’s finest moment on film.

Beatles Handbook rating: 4 Stars

Essential tracks

A Hard Day’s Night

I should Have Known Better

If I Fell

And I Love Her

Can’t Buy Me Love

Things We Said Today

I’ll Be Back

Buy this album: Hard Day’s Night

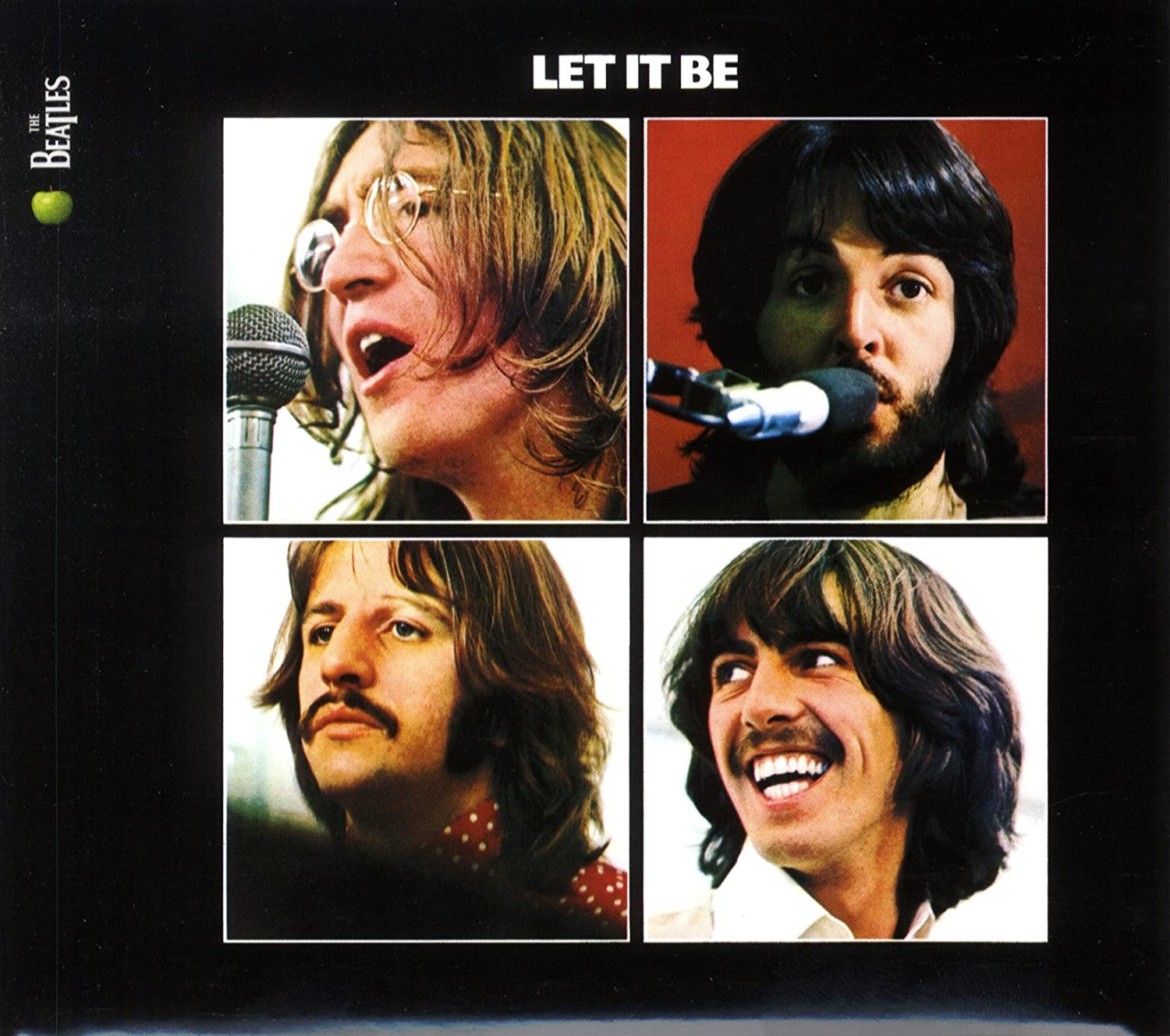

An album that includes songs of the quality of ‘Across The Universe’, ‘Let It Be’, ‘The Long and Winding Road’ and ‘Get Back’ should rate five stars, but it’s actually somewhat of a disappointment. The inclusion of two sub-one minute tracks (‘Dig It’ and ‘Maggie Mae’), a piece of Lennon juvenilia in the form of ‘One After 909’, and Harrison’s lightweight ‘For You Blue’ gives Let It Be an uneven quality. That’s exacerbated but the inclusion of second division songs (at least in the context of The Beatles catalogue) ‘Dig a Pony’ and ‘I’ve Got a Feeling’, but it’s hardly surprising once you’ve seen the film Get Back and understand the chaotic nature of the rehearsal and recording sessions for the album. McCartney’s touching and wistful ‘Two of Us’ and Harrison’s waltzing ‘I Me Mine’ are the album’s two relatively hidden gems.

Beatles Handbook rating: 3 stars

Essential tracks

Two of Us

Across The Universe

I Me Mine

Let It Be

The Long and Winding Road

Get Back

Buy this album: Let It Be

Where to start with The Beatles by The Beatles? An album that sounds like an extended re-issue of itself with bonus tracks that should never have seen the light of day (WTAF is Wild Honey Pie?). Starting at the beginning is actually a very good idea as you get to hear ace rocker ‘Back In The U.S.S.R’., the dreamy psychedelia of ‘Dear Prudence’ and the archly self-referential ‘Glass Onion’. Then the problems start. Oh bloody hell, it’s ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’, McCartney at his absolute worst, culturally appropriating a story that’s not his to tell over a weird and horrible umpah-meets-cod-reggae backing track. Jesus wept. At least the aforementioned ‘Wild Honey Pie’, the next track up, with its faux avant garde stylings has the decency to last a merciful 53 seconds.

I’m not going parse all 30 tracks of this sprawling mess, but suffice to say that to get to every magnificent song such as Harrison’s ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, Lennon’s ‘Julia’ or McCartney’s ‘Blackbird’ you have to wade through dreck like ‘The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill’ or the more than eight unlistenable minutes of ‘Revolution 9’ (if anyone tries to tell you that, actually, that’s their favourite Beatles song, run). It is however almost worth the slog to end up at one of the loveliest songs the band ever recorded, ‘Good Night’, affectingly sung by Ringo.

Beatles Handbook rating: 3 stars

Essential tracks

Back In The USSR

Dear Prudence

While My Guitar Gently Weeps

Happiness Is A Warm Gun

Martha My Dear

Helter Skelter

Julia

Mother Nature’s Son

Everybody’s Got Something to Hide

Revolution 1

Cry Baby Cry

Good Night

Buy this album: The Beatles

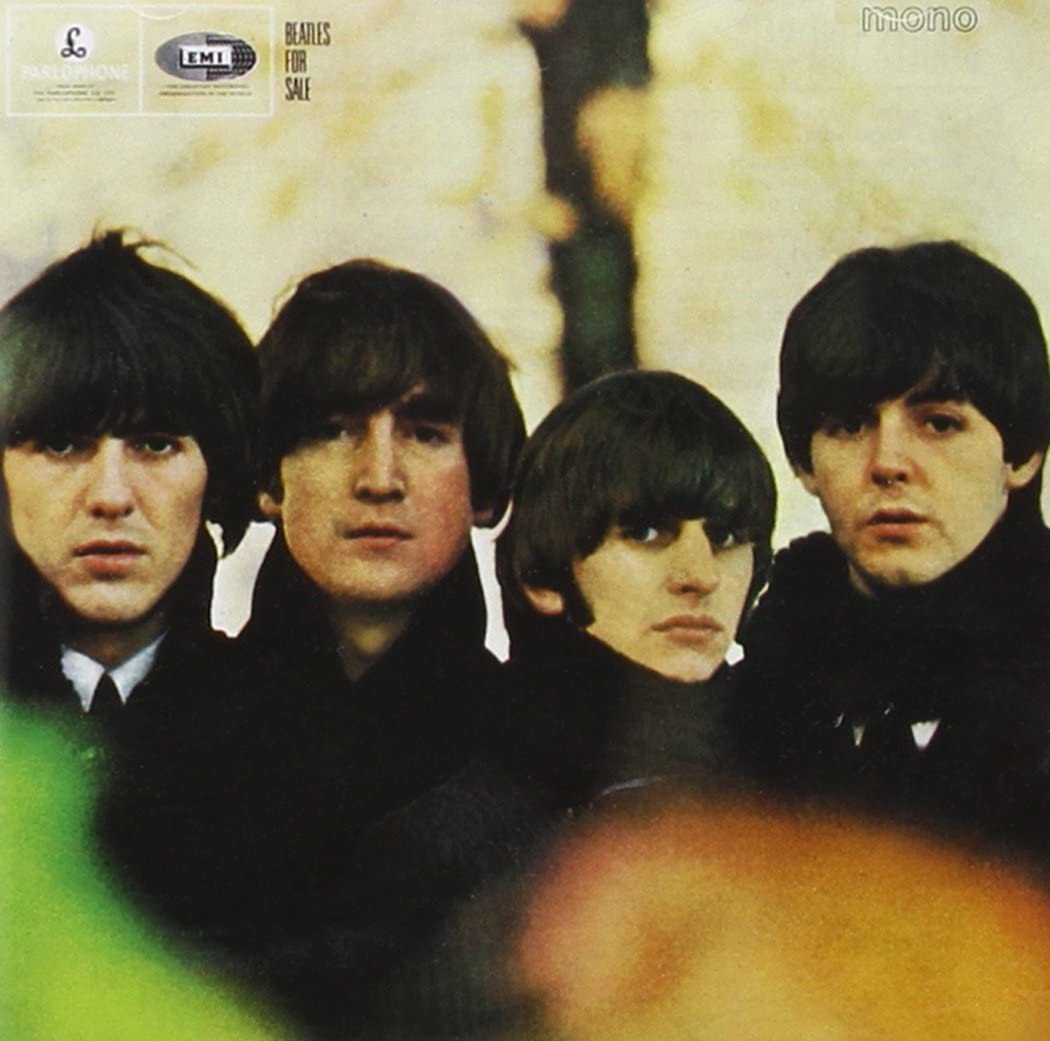

Sorry, I’m not buying. Compared to the giant leap forward that was A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles For Sale is a big step back. But let’s be fair; it was released just 21 weeks after Hard Day and was the fabs fourth album in two years. No wonder they resorted to padding out the 33 minute running time with no less than six cover versions. We are sadly back in Hamburg it seems, but at least Chuck Berry’s ‘Rock’n’Roll’ and Leiber/Stoller/Penniman’s ‘Kansas City’ sound convincingly raucous. The less said about Ringo’s rather painful stab at Carl Perkins’ ‘Honey Don’t’ the better. Of the originals, ‘Eight Days a Week’ is the obvious stand out but the nakedly vulnerable, confessional lyrics of ‘I’m A Loser’ are striking, ‘Every Little Thing’ is a beautifully constructed pop song full of hooks, and Harrison’s twelve string riff gives ‘What You’re Doing’ a distinctive sound that would be much copied by the likes of The Byrds.

Beatles Handbook rating: 3 stars

Essential tracks

No Reply

I’m A Loser

I’ll Follow The Sun

Eight Days a Week

Every Little Thing

What You’re Doing

Buy this album: Beatles for Sale

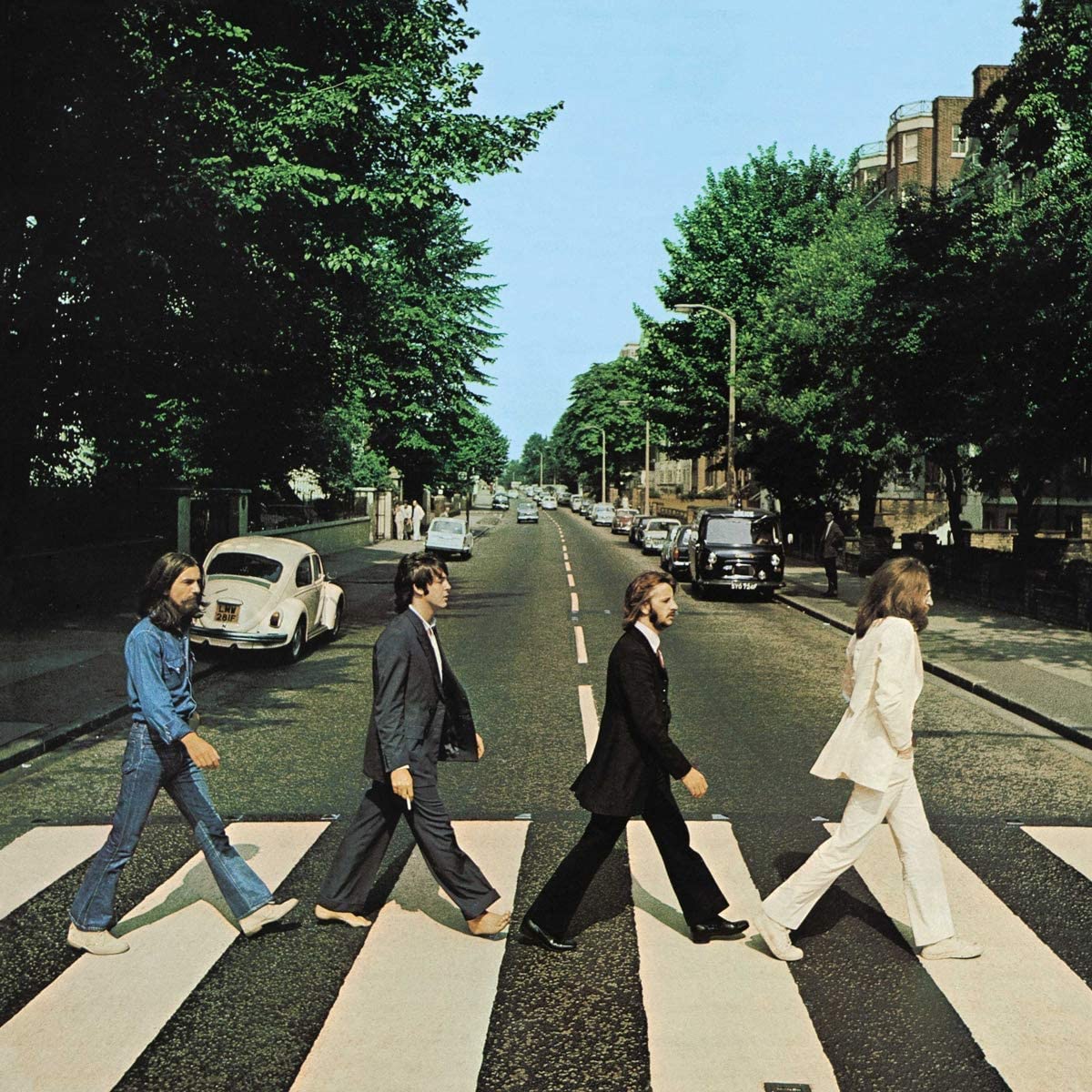

8 Abbey Road

The band’s final recordings (although penultimate release; Let It Be appeared eight months later) are sadly a rather scrappy affair. Harrison comes out on top with two stone cold, all time classics in ‘Something’ and ‘Here Comes The Sun’, not only the best songs on the album, but among the best he ever wrote and among the best of the entire Beatles catalogue. Lennon’s strident ‘Come Together’ makes an ear-grabbingly effective opener, especially with Ringo’s rolling drum pattern, one of the most famous in pop history.

Beyond that, things get rather messy. Apart from inventing three chord punk nearly a decade before the Sex Pistols with ‘Polythene Pam’, there is McCartney’s music hall fetish in the form of ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’, the white man’s doo-wop of ‘Oh! Darling’ and whatever the hell ‘Octopus’s Garden’ is meant to be to contend with. Not to mention a patience-testing 7 minutes 47 seconds of ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’, although the extended instrumental outro is pretty mesmerising.

There are some stunning moments scattered around, ‘Sun King’ is a rather lovely thing, reminiscent of Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Albatross’, and there are some great melodies on ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ and ‘Golden Slumbers’, but ultimately the album fails to cohere in the same way as Revolver or Help!.

Beatles Handbook rating: 3 Stars

Essential tracks

Something

Here Comes The Sun

Sun King

You Never Give Me Your Money

Golden Slumbers

Buy this album: Abbey Road

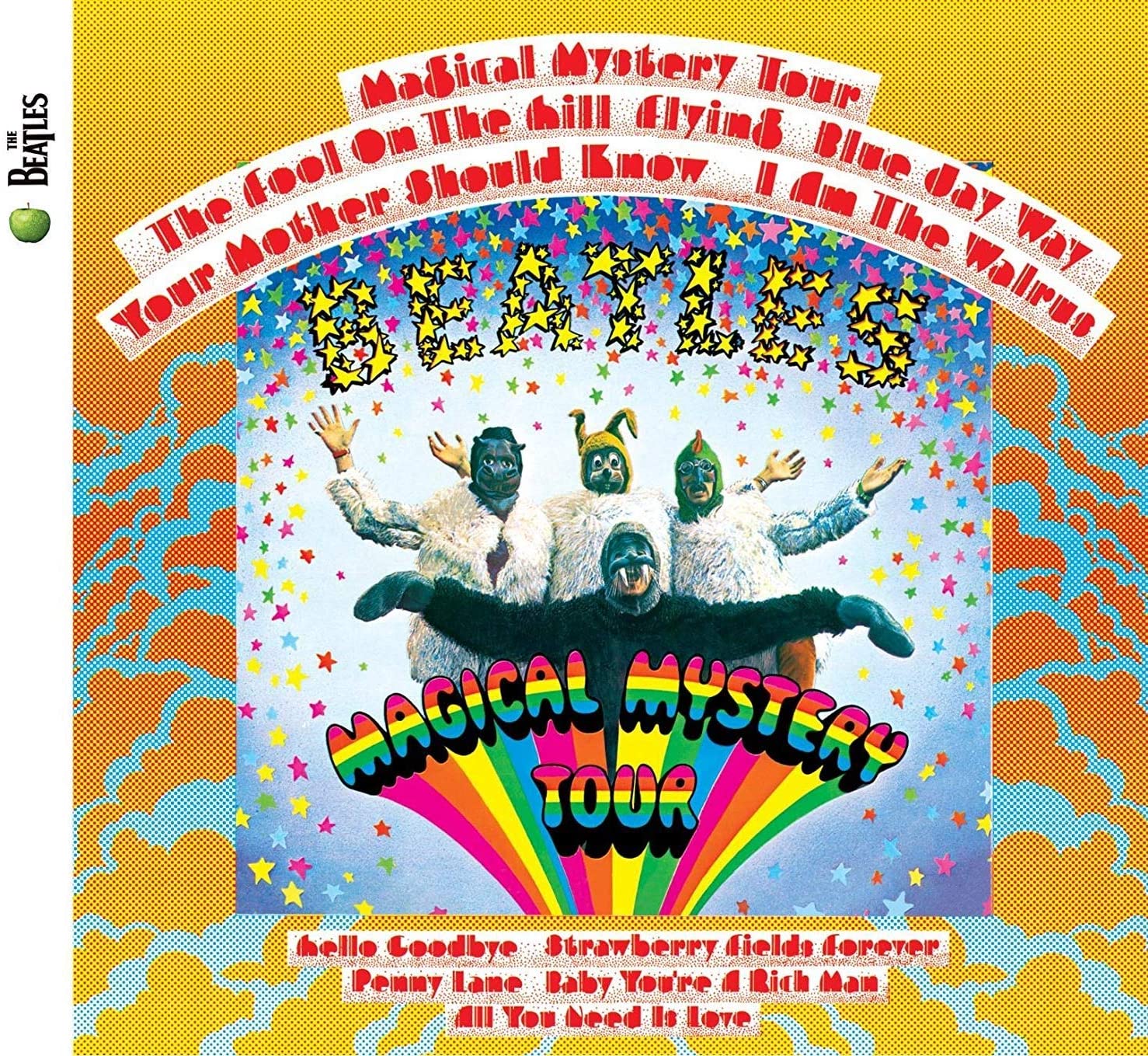

Not a full studio album as such but a compilation of a double ep soundtrack to a made-for-TV film plus some singles. It might be a bit of a mess thematically (as is the film itself, and that’s putting it mildly) but that’s hardly a rare trait in the Beatles album canon and it does contain some of The Beatles best-known songs. The original British ep release not only included the rousing title track (a far better signature tune for a concept than St. Pepper’s) but ‘The Fool On The Hill’ one of McCartney’s greatest and most unusual compositions, ‘I Am The Walrus’, Lennon’s most successful stab at musical and lyrical surrealism, and Harrison’s remarkable, woozy and weird ‘Blue Jay Way’ (is there anything in pop or rock that sounds quite like it?).

The collection of non-album A and B sides that make up the rest of the album is almost ridiculous in terms of its quality. ‘Hello, Goodbye’, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘All You Need Is Love’ are of course among the cream of the Beatles crop; even ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’, the B-side of ‘All You Need Is Love’ is a cracker.

Because it’s status as an album is questionable and having all those non-album singles on it is sort of ‘cheating’ in the context of the band’s other releases which lack that advantage, it appears lower down on this list than it might do. A great listen, especially for those whose favourite Beatles album would be ‘The Best of The Beatles’.

Beatles Handbook rating: 4 stars

Essential tracks

The Fool On The Hill

I Am The Walrus

Blue Jay Way

Hello, Goodbye

Strawberry Fields Forever

Penny Lane

All You Need Is Love

Buy this album: Magical Mystery Tour

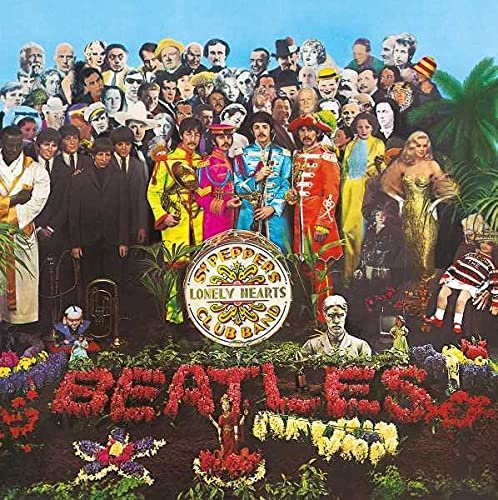

The first Beatles album I bought as a kid, aged 11. I never really liked it and now, more than four decades years later, I still don’t. It sounds to me like a band losing their way; the Sgt Pepper’s conceit merely a way of bringing some sort of cohesion to a very disparate group of songs written by musicians with one eye on the exit door. You can either view the juxtaposition of ‘Within You Without You’ and ‘When I’m Sixty Four’ as audacious and daring or simply desperate. ‘Lucy In The Sky’ has aged badly into try-hard psychedelia; ‘Fixing a Hole’ is uninspired, lumbering and mundane, ‘She’s Leaving Home’ is a re-tread of the vastly superior ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and ‘Being For The Benefit of Mr. Kite!’ is much less clever and much less listenable than Lennon probably thought it was. ‘A Day In Life”s haunting refrain is swamped by over production and the unwelcome intrusion of McCartney’s ‘middle eight’. It’s a striking, innovative piece but I’m not sure I’d ever want to listen to it for fun. It’s another album that would make a great EP with ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ and Ringo’s touchingly performed vocal providing the lead track.

Beatles Handbook rating: 3 stars

Essential tracks

With A Little Help From My Friends

Getting Better

Lovely Rita

Good Morning Good Morning

Buy this album: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

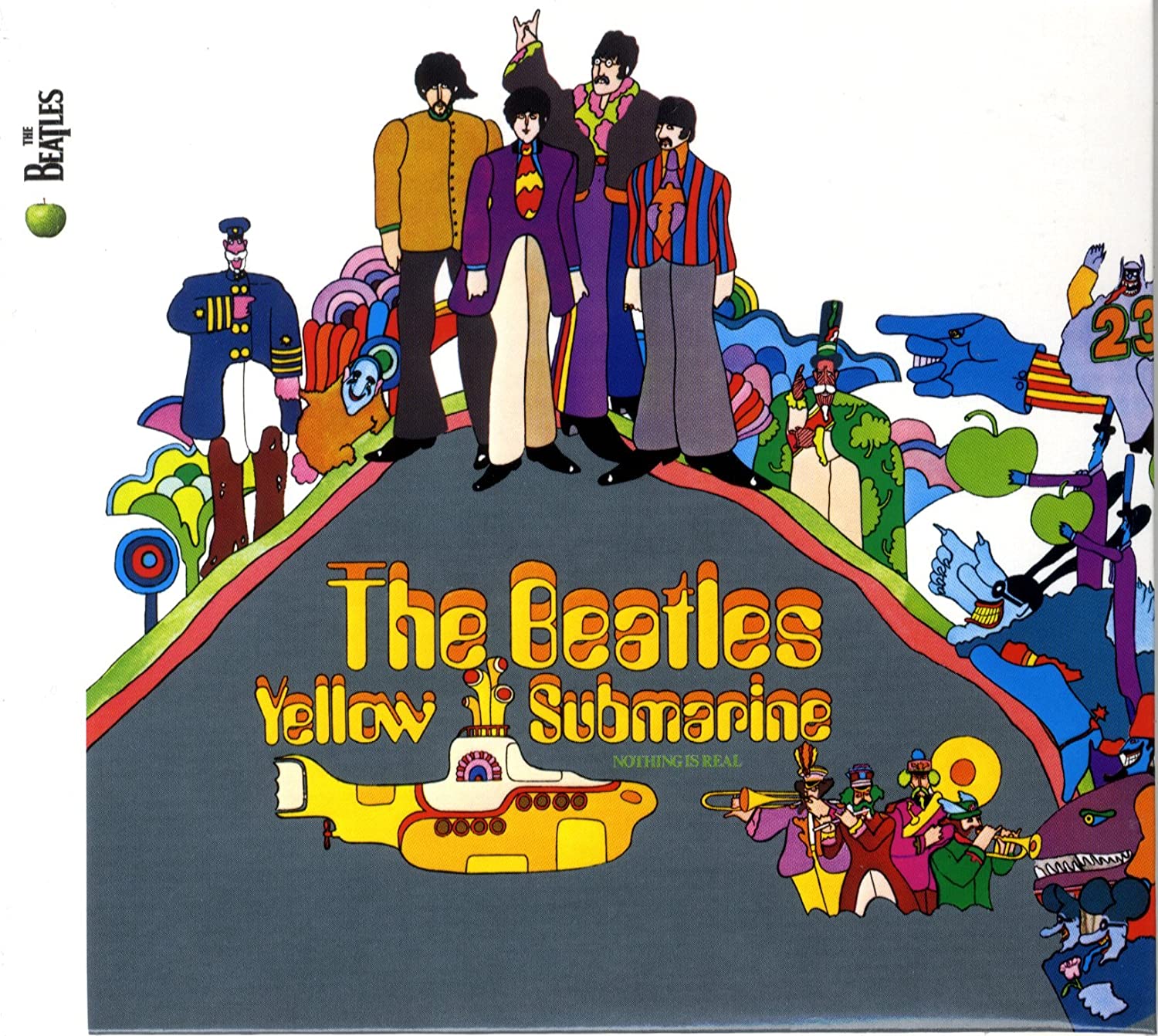

A curio in The Beatles album canon. The soundtrack to the animated film contains only four previously unreleased songs, the rest of the running time made up from the title track, which previously appeared on Revolver, ‘All You Need Is Love’ which was a single and also collected on Magical Mystery Tour, and George Martin’s instrumental orchestral music for the film, none of which will be troubling us here. Unusually, Harrison gets two out of the four new cuts and both are very decent examples of late period Beatles. The inventive and unusual ‘Only A Northern Song’ is built around a loping bassline and random-sounding soundscape of squawling trumpets and backwards tape loops that is much easier on the ear than that description might sound. ‘It’s All Too Much’ is a medium paced stomper with a droning organ riff and busy percussion track supporting a lilting verse melody and catchy chorus hook that all adds up to a distinctive and enjoyable addition to the bands catalogue. ‘Hey Bulldog’s driving piano riff underpins a snarling, menacing Lennon vocal to great effect, but McCartney’s throwaway knees up ‘All Together Now’ irritates rather than amuses. One for Beatles collectors rather than the general listener.

Beatles Handbook rating

3 Stars

Essential tracks

Northern Song

Hey Bulldog

It’s All Too Much

Buy this album: Yellow Submarine

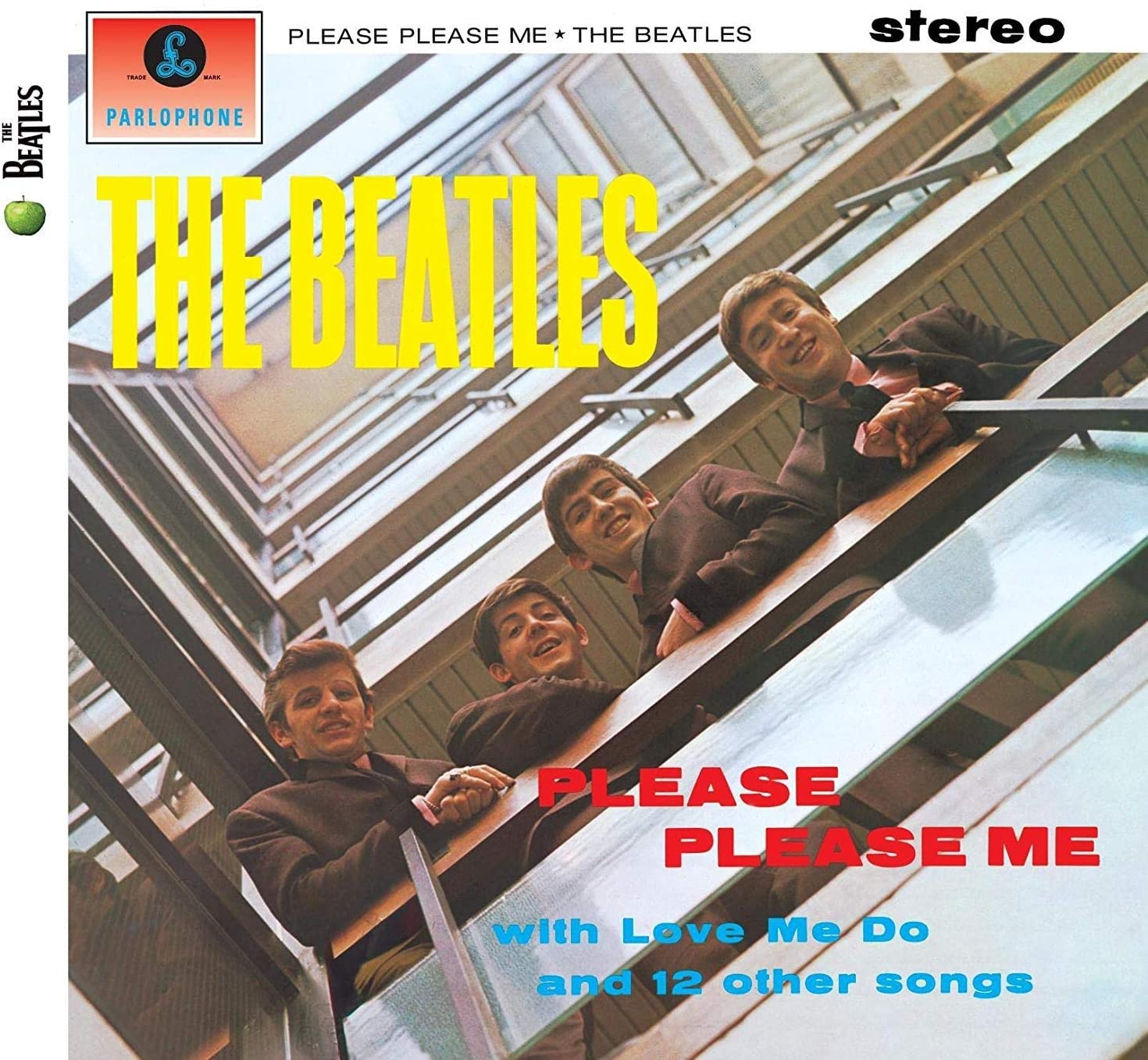

Beatles Handbook rating

2 Stars

Essential tracks

Please Please Me

Do You Want To Know A Secret

Baby It’s You

Boys

There’s A Place

Buy this album: Please Please Me

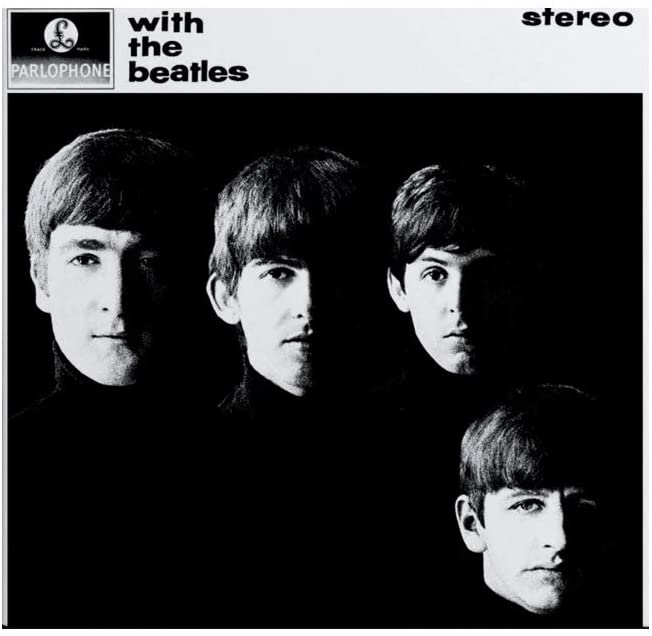

Released eight months after Please Please Me, the band’s second album sticks pretty much to the debut’s formula with again, eight originals and six covers including Chuck Berry’s ‘Roll Over Beethoven’. It’s a similar mix of rockers and sappy love songs but this time there’s a high quotient of original top pop tunes including the urgent opening track ‘It Won’t Be Long’, the timeless classic ‘All My Loving’ and Harrison’s sombre and relatively overlooked ‘Don’t Bother Me’. But as an album, it still sounds too much like it’s based around a got-to-please-them-all Hamburg set list.

Beatles Handbook rating

2 Star

Essential tracks

It Won’t Be Long

All My Loving

Not a Second Time

Don’t Bother Me

Buy this album: With The Beatles